[ad_1]

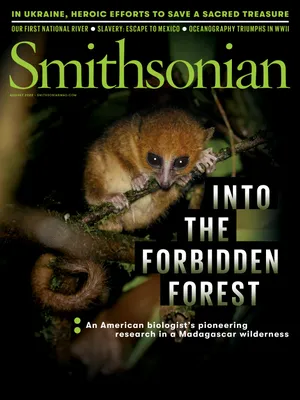

Diana Cardenas, a high school English teacher from Pharr, Texas, stands in her small family cemetery between the Rio Grande and the new border wall. Stylishly dressed and coiffed, wilting slightly in the heat and humidity, she holds up a photograph of her grandmother. “Her name was Adela Jackson, and we were close,” she says. “She loved to come here, and tell me stories about our family history, and all the runaway slaves we helped and took across the river into Mexico.”

Until recently, the southbound Underground Railroad, as some scholars call it, has been largely overlooked, mainly because it left so few traces in surviving records. No one who escaped slavery by going to Mexico wrote a firsthand account of the experience, as Frederick Douglass and others did about escaping north. Nor were they interviewed by researchers, or recruited by antislavery organizations. And though the journeys of enslaved people to Mexico are of the utmost importance, the scale of the southern migration was more modest, numbering between 3,000 and 10,000 people, compared with an estimated 30,000 to 100,000 who fled north of the Mason-Dixon line.

But in recent years scholars have begun to uncover a wealth of information about the southbound freedom-seekers. For example, they’ve learned that while there was no organized network of assistance, no celebrated “conductors” like Harriet Tubman guiding them to the next safe haven, slaves escaping to Mexico did sometimes receive help along the way.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/79/4a/794a082b-a625-4e4a-a9cd-9bf63e615665/julaug2022_c10_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

Diana Cardenas at the grave of her great-great-great-grandfather Nathaniel Jackson, a white settler who owned a ranch in Texas near the Rio Grande.

Scott Dalton

Diana Cardenas’ great-great-great-grandfather, who died in obscurity, was among the staunchest allies of slaves escaping south. “He was a white man from Alabama named Nathaniel Jackson,” says Cardenas. “He married a slave that he freed, Matilda Hicks, and they came out here in covered wagons in 1857. She already had three children by another man, and she had seven more with Nathaniel.”

Cardenas produces a faded, blurry, copied photograph of Matilda Hicks, her great-great-great-grandmother, as an old woman, tall and thin and wearing a white dress.

“Nathaniel bought 5,535 acres of land right here by the river and established the Jackson Ranch,” says Cardenas. “There were Black, white and mixed-race people all living together, raising cattle in a place that was very remote, where they could be left alone. The runaways knew they could get help here—food, clothing and work if they wanted it. Nathaniel was a nice, generous, courageous man, a humanitarian. He would cross them into Mexico in boats.”

The history of southbound runaways, preserved in scattered fragments, presents scholars with enormous challenges of research and interpretation. Perhaps no one has done more to advance our understanding than a historian named Alice Baumgartner. In 2012, as a Rhodes scholar studying violence on the U.S.-Mexico border in the early and mid-19th century, she was hunting through state and municipal archives in northern Mexico. She found plenty of documents about cattle rustling and Lipan Apache raids, but she also came across records of a completely unexpected kind of violence—between American slave catchers crossing the Rio Grande and Mexicans who fought against them.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/42/47/42471836-7102-4834-ab1c-12bbe11650cc/julaug2022_c09_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

Cardenas holds a photo of her great-great-great-grand-mother Matilda Hicks, a former slave. Hicks and husband Jackson helped many Black people flee slavery.

Scott Dalton

“It really caught my attention, because I didn’t know that enslaved people were escaping into Mexico, and I never would have suspected that Mexican citizens and officials were protecting them,” says Baumgartner, now an assistant professor of history at the University of Southern California.

She was particularly struck by the story of Manuel Luis del Fierro of Reynosa, in the state of Tamaulipas, who was startled awake by screaming on the night of August 20, 1850. He threw off the covers, grabbed his rifle and confronted two men in his living room. One was waving a pistol at his wife’s maid, a young Black woman named Mathilde Hennes, who had escaped slavery in Louisiana, made the long, dangerous journey to Mexico, and become a valued member of Del Fierro’s household.

Pointing his rifle at the kidnappers, Del Fierro ordered them to surrender. One got away, but the other—William Cheney of Cheneyville, Louisiana, who claimed Hennes as his property under U.S. law—was arrested by the Reynosa police, imprisoned for nearly a month, and sent home empty-handed.

The incident was not unusual, Baumgartner discovered. She read the correspondence of four councilmen from the Mexican border town of Guerrero, who pursued, shot and killed a slaveholder who had kidnapped a runaway. In 1851, the residents of another village in the state of Coahuila took up arms to stop a slave catcher named Warren Adams from abducting a Black family. Months later, the Mexican Army posted a sizable force and two artillery pieces on the Rio Grande to prevent a group of 200 Texans from crossing the border to seize runaway slaves.

Baumgartner kept uncovering information that surprised and fascinated her. After independence from Spain, in 1821, “Mexico passed these really radical antislavery laws, and Mexicans at all levels of society were serious about enforcing them,” she told me recently. “This was well known by enslaved people on the U.S. side of the border.” Indeed, more than three-quarters of the fugitive slaves caught in Texas between 1837 and 1861, she learned from a database of runaway slave notices, were heading to Mexico.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f8/d8/f8d81b71-f828-46c2-b9e5-bbafba1c60e7/julaug2022_c13_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

Felix Haywood, who was enslaved in Texas, recalled hearing tales of those who escaped to Mexico. They “got on all right,” he told an interviewer in 1937.

Library of Congress

Baumgartner went on to search 28 archives in three countries—Mexico, the United States and Britain—and wrote the first full-length book about the subject, South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War. The book, published in 2020, was lauded for its groundbreaking historical insights and panoramic sweep. “Masterfully researched,” wrote a reviewer for the New York Times. Publishers Weekly called it “an eye-opening and immersive account.” “Black Perspectives,” the digital publication of the African American Intellectual History Society, argued that it made “a convincing case that Mexico shaped the freedom dreams of enslaved people in states like Texas and Louisiana.”

At the heart of Baumgartner’s study were a few simple questions: “Why were enslaved people escaping to Mexico?” she says. “What did they find there? Why were Mexicans helping them?”

Felix Haywood of San Antonio, a former slave interviewed in 1937 for the Federal Writers’ Project, didn’t himself try to escape south, but he heard stories about those who did, and he visited Mexico after the Civil War before returning to Texas. “There wasn’t no reason to run up North,” he told the interviewer. “All we had to do was walk, but walk South, and we’d be free as soon as we crossed the Rio Grande. In Mexico you could be free. They didn’t care what color you was—black, white, yellow or blue.”

The earliest examples of slaves escaping south are from the late 17th century. In the Carolinas, enslaved men and women ran away from the rice plantations to Spanish Florida, where they were able to arm themselves against their former enslavers. In 1693 King Charles II of Spain decreed that all fugitive slaves would be free in Florida. In 1733 a caveat was added: To gain their freedom, fugitives had to convert to Catholicism and declare loyalty to the Spanish crown. In 1750 the same promise was extended to the entire Viceroyalty of New Spain, which included all of present-day Mexico and nearly all of the American West, plus Florida.

After the Louisiana Purchase, in 1803, the de facto border between the United States and New Spain was the Sabine River, in present-day East Texas. (This border was formalized in 1819.) It’s impossible to say how many enslaved people made it across the Sabine, but we know that slaveholders in Louisiana complained about escapes to New Spain. Thomas Mareite, a French historian at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany, has found evidence that 30 slaves from plantations on the Cane River near Natchitoches left for New Spain in October 1804. Nine crossed the Sabine River, and a string of similar escape attempts followed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/54/6d/546de218-7131-483a-9453-81be6045b017/julaug2022_c02_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

The Cane River near Natchitoches. Between 1804 and the Civil War, some people enslaved at plantations by the river sought asylum in Mexico.

Scott Dalton

In January 1808 a Black man recorded as “Rechar,” presumably Richard, arrived at Trinidad de Salcedo, a small Spanish outpost near present-day Madisonville, Texas. He told his story to the authorities. His family had been split up by enslavers and scattered all over southern Louisiana. Having made his own escape from a plantation in Opelousas, he managed to find and rescue his wife and three of their seven children. He tried, and failed, to rescue the other four, then led his reduced family across more than 100 miles of swampy wilderness and crossed the Sabine River into freedom. (Their fate in Spanish territory is unknown.)

Even though slavery existed in New Spain, American runaways were usually granted asylum by the Spanish authorities, because the American form of slavery was regarded as far more brutal and dehumanizing. In New Spain, for example, slaves were subjects of the Spanish crown, not property, and it was illegal to separate husbands and wives or to impose excessive punishments. Rechar declared that “the harshness of American laws” as well as keeping his family together were the reasons for his escape.

In 1821, after Mexico won its independence, it opened the northern frontier state of Tejas (as Texas was then called) to Anglo American settlers. Many of those settlers brought Black slaves and established American-style cotton plantations in present-day East Texas. This set up a conflict with the Mexican government, which banned the importation of enslaved people in 1824, on the principle of liberty for all.

The Anglo colonists ignored the law or imposed lifetime contracts of indentured servitude on their Black workers. The state of Coahuila y Tejas responded by limiting indenture contracts to ten years, and guaranteeing liberty to the children of slaves, in a so-called “free womb” law. In 1835, the Anglo settlers, bristling at these and other laws they regarded as oppressive, rose up in revolt. “It’s controversial, especially in Texas, but the historical profession is coming to a consensus that slavery was an important part of the Texas Revolution,” says Baumgartner.

In 1836, Texas won independence from Mexico and, now an autonomous republic, enshrined slavery in its constitution. Mexico fully abolished slavery the following year. In 1845, Texas joined the United States as a slave state. Then came the Mexican-American War of 1846-48. Defeat forced Mexico to relinquish all or parts of the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Wyoming.

“This was the first time in its history that the U.S. acquired territory where slavery was [previously] abolished by law,” says Baumgartner.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/65/cd/65cdc2e0-c96b-4528-8a40-b878a423e6a5/julaug2022_c99_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

Black people enslaved in the United States improvised several routes to Mexico in pursuit of freedom.

Guilbert Gates; Map Source: © Thomas Mareite

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/7f/8f7f63a9-b5ce-4750-a9d1-3cda223e124f/julaug2022_c08_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

Workers tend to onion crops on land that was once part of the Jackson Ranch, near Pharr, Texas. The East Texas border town now connects by bridge to the Mexican city of Reynosa.

Scott Dalton

At the same time, Southern politicians attempted to expand slavery by annexing Cuba, where it was firmly entrenched, and by working to overturn the Missouri Compromise, which had prohibited slavery in much of the territory acquired in the Louisiana Purchase. When these and other efforts failed, secession and Civil War followed.

The idea that Mexico’s antislavery laws not only encouraged African American slaves to cross the southern border but also ignited the Texas Revolution and inflamed the conflict between North and South that led to the American Civil War is the essence of Baumgartner’s groundbreaking argument. “It reorders the way we should think and teach about the slavery expansion crisis,” David Blight, the Yale historian and Pulitzer Prize-winning author of 2018’s Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, says. “Indeed, it reorders how to think about the huge question of the coming of the American Civil War.”

In 1849, Mexico’s congress decreed that foreign slaves would become free “by the act of stepping on the national territory.” This soon became common knowledge among enslaved people in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and what would later become Oklahoma. They envisioned what historian Mekala Audain calls a “Mexican Canaan” across the Rio Grande—a promised land where they could be free. They made the arduous journey through Texas. They stowed away on boats leaving from Galveston and New Orleans for Tampico and Veracruz. In the 1850s a dozen slaves were reaching Matamoros, Mexico, every month. Two-hundred-seventy arrived in Laredo, in Tamaulipas (now called Nuevo Laredo, just across the border from Laredo, Texas) in a single year. American diplomats kept pressuring their Mexican counterparts to sign extradition treaties, which would return runaway slaves to their owners, but Mexico flatly refused—in 1850, 1851, 1853 and 1857.

Audain, an associate professor at the College of New Jersey, is currently finishing a book about the experiences of enslaved African Americans in the Texas-Mexico borderlands. “One distinct aspect of escapes in Texas was navigating the terrain,” she says. “Depending on where they began their escapes, there could be limited shade and water, especially as they traveled south of San Antonio. A lack of trees also limited their abilities to camouflage themselves.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9c/64/9c644420-21a8-458f-b830-36262994952d/julaug2022_c05_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

To enslaved people fleeing to Mexico, the dry, snake-infested desert from the Nueces River to the Rio Grande was one of the most dangerous parts of the trip.

Scott Dalton

There were several different routes to Mexico. Slaves escaping from Louisiana tended to go via Nacogdoches to Houston and cross the border to Matamoros. Another route went from the vicinity of Austin to San Antonio and then to Laredo in Tamaulipas or Piedras Negras in Coahuila. Using established roads, or keeping them in sight, made it easier to navigate, but increased the likelihood of confrontation and capture.

Most northbound runaways were on foot and unarmed, but many southbound freedom-seekers, especially from Texas, rode horses and carried guns. “It was a reflection of the culture and the most effective strategy,” says Audain. “They could travel faster, defend themselves and hunt for food.” Escaping on horseback probably also helped to neutralize the much-feared bloodhounds and other slave-hunting dogs; the dogs had no clear human scent to follow and likely couldn’t keep up with horses over long distances.

Kyle Ainsworth, a historian and special collections librarian who runs the Texas Runaway Slave Project at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, has calculated from runaway slave notices that 91 percent of Texas escapees were male, with an average age of 28. “Many women were responsible for raising their children,” says Ainsworth. “It was very difficult for enslaved people to run away with young children, although there are definitely a few examples where they tried.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/9f/8d9f63ff-f7df-443d-a6b4-51b0c29bc426/julaug2022_c11_undergroundrailroad_copy.jpg)

A notice in a Texas newspaper published in 1852, three years after Mexico promised that enslaved people who made it across the border would be free.

Texas Runaway Slave Project

Baumgartner has noted the ingenuity many escaping slaves showed. “They forged passes to give the impression they were traveling with the permission of their masters. They disguised themselves as white men, fashioning wigs from horsehair and pitch. They stole horses, firearms, skiffs, dirk knives, fur hats, and in one instance, 12 gold watches and a diamond breast pin.”

Some fugitives were helped by other slaves, free Black people, Mexicans, Germans and other sympathetic white people, but these allies operated independently of one another and risked being tarred, feathered, hanged or shot for helping slaves escape. One former slave who made it to Chihuahua, Mexico, and was later captured, said mail carriers helped him escape, but this appears to be an isolated example.

For the great majority, the journey south was an improvisation, a wayfinding through an unknown and hostile geography. They lived by their wits on a constant knife-edge of danger; for those on foot, the journey could take months. Often pursued by their enslavers, or hunted by slave patrols, with a bounty on their heads that any citizen might attempt to collect, they had to find food and water and contend with the Texas climate—well over 100 degrees in summer and subject to sudden, freezing “blue norther” storms in winter. Native Americans were another threat.

The most dangerous part of the journey was the Nueces Strip—a 100- to 150-mile expanse of remote, thorny, rattlesnake-infested brush country between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. It contained few roads or settlements, which made it hard to navigate and find food, and very little water. There was no slavery this far south in Texas, because the risk of slaves escaping to Mexico was too great. Black people were highly conspicuous and immediately suspected of being fugitives. “The Nueces Strip was also where runaway slaves were most likely to encounter slave catchers, military patrols, Texas Rangers and Indians—all of whom would capture them or worse,” says Ainsworth.

If they reached the Rio Grande near present-day Pharr, Texas, runaways could expect help and kindness from Nathaniel Jackson and his neighbors, but the river ran for more than 1,000 miles along the international border, and most runaways reached it elsewhere. For Audain, the most affecting stories are those that end with drownings in the Rio Grande. “I think of all the effort they put into planning their escapes, walking hundreds of miles across Texas, and managing to avoid kidnappers and patrols,” she says. “They somehow survived these challenges, only for their journeys to end not with freedom, but with death.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0f/00/0f0030cf-d781-4d41-a1c6-e33d10e6172d/julaug2022_c12_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

The last, often lethal obstacle: the Rio Grande, shown near land owned by Nathaniel Jackson and John Webber, who ferried many enslaved people across.

Scott Dalton

Mareite, the French historian, uses the phrase “conditional freedom” to describe what runaway slaves found in Mexico. Alice Baumgartner compares it to the abridged freedom that runaways found north of the Mason-Dixon line, where the U.S. Constitution, through the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850, provided for their capture and return to slavery. In Mexico, federal law guaranteed freedom to runaways, but they were always at risk from North American slave hunters who crossed the border illegally and broke Mexican antislavery laws.

Most runaways arrived in Mexico with little or no Spanish. A few were able to establish themselves as merchants, carpenters and bricklayers in Matamoros and other cities. For the great majority, however, there were two options. They could find work as servants or day laborers on ranches and haciendas. Or they could risk their lives once again by joining military colonies.

These were fortified outposts established by the Mexican government to defend its northeast borderlands from devastating raids for livestock, captives and plunder by Comanches and Lipan Apaches. In return for such military service, according to a law passed by Mexico’s congress in 1846, foreigners, including runaway slaves, would receive land and full citizenship. Historians know little about the experiences of African Americans in these military colonies, with one significant exception.

At a colony in Coahuila were Black Seminoles, descended from free Black people and slaves who had run away from Georgia and the Carolinas and allied themselves with the Seminole Indians in Florida. They had fought with the tribe in the three Seminole Wars against the U.S. Army. When they were finally defeated, the Seminoles and Black Seminoles were forced onto the Creek reservation in Indian Territory, in present-day Oklahoma, with most arriving by 1842. The Creeks denied the newcomers land and started capturing Black Seminoles and selling them into slavery in Arkansas and Louisiana. By 1849, says Baumgartner, “the Seminoles and their Black allies had had enough.”

The Seminole leader Wild Cat, with the assistance of John Horse, leader of the Black Seminoles, led more than 300 men, women and children, including 84 Black Seminoles, from Indian Territory south to Mexico. In northern Coahuila, the Mexican government granted them a 70,000-acre military colony with work animals, agricultural equipment and financial subsidies. Within months of arriving, Wild Cat went back to Indian Territory and returned with about 40 more Seminole families and most of the remaining Black Seminoles.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f3/69/f369358b-5d31-41ee-a756-6aac7ef74a9a/julaug2022_c14_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

The Black Seminole leader John Horse, who helped lead Black and Native Seminoles to Mexico, where the government gave them land in exchange for military service.

Alamy

Runaway slaves started arriving before the colonists had finished clearing fields and building their wood-frame houses. One man named David Thomas had escaped with his daughter and three grandchildren. In 1850, a group of 17 arrived, asking to join the Black Seminoles. By 1851, there were 356 Black people living at the colony, and three-quarters of them were runaway slaves. At a moment’s notice, all the adult males had to be ready to fight against the Comanches or Apaches, arguably the most formidable Native American warriors on the continent.

In her book, Baumgartner describes an early morning scene at the outset of a military campaign: “bright-kerchiefed heads appeared in the low doorways of the houses; women unhobbled the horses, slipping bits into their mouths. Then the men emerged, a powder horn and a bullet pouch slung across a shoulder, a machete or a horse pistol in hand.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fa/19/fa198001-790c-424e-a12a-c5a5e4eb7476/julaug2022_c04_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

The manor house at the Oakland Plantation, near Natchez, Louisiana. Records show that 162 people were enslaved at the plantation in 1864.

Scott Dalton

The Black Seminoles, known as Mascogos in Mexico, had a well-earned reputation as superb trackers and fighters. On foot or on horseback, according to the historian Kenneth Porter, who gathered their oral histories in the 1940s, the stronger men would use muskets as clubs. “They beat down buffalo-hide shields, splintered lance shafts, and rammed the iron-shod stocks into their enemies’ astonished faces.” Others used machetes to hack off spear and lance points, and then decapitate their foes. In a battle known in the oral history as “the big fight,” 30 or 40 Black Seminoles defeated a much larger force of Comanches and Apaches, and much of the fighting was hand-to-hand combat.

Descendants of the Black Seminoles and the runaways who joined them are still living in the town of El Nacimiento de los Negros (literally The Birth of the Blacks) in northeast Coahuila. Every year on June 19 they stage a celebration with dancing and barbecues. The women dress up in long, polka-dot pioneer dresses. The children sing songs in an old African American dialect of English that can be found in Negro spirituals. Only recently, according to Baumgartner, did the villagers learn their tradition is connected to Juneteenth, which celebrates the end of slavery in the United States. “In Nacimiento, it’s called Día de los Negros or Day of the Blacks,” she says.

In Porter’s unpublished oral histories, which Baumgartner was thrilled to find in an archive at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, people in El Nacimiento describe cultural traditions that date back to slavery. “Even though they’re in a Catholic country, with a priest posted in their community to make sure they’re good Catholics, they’re still celebrating the marriage ceremony by jumping over the broomstick,” says Baumgartner.

Thanks to Porter, Baumgartner was able to conjure the lives of the Black Seminoles and the runaways in their colony. But she found no detailed source material about other African Americans in Mexico, and has failed to find any other descendants. “Many of them took Spanish names and married into Mexican families,” she says. “And the Mexican government stopped keeping track of anyone’s race in 1821 with official documentation.”

With enslavers, Texas Rangers, bounty hunters and slave catchers all crossing the border to kidnap runaways in Mexico, the last thing Black refugees wanted to do was advertise their presence. They lived as discreetly as possible. “They evaded their enslavers for the same reason they’re evading historians,” says Baumgartner. “It’s hard to get too mad about that.”

A mockingbird calls from a mesquite tree in the graveyard as the sun sets over the Rio Grande. The manicured hand of Diana Cardenas goes back into her folder of photographs and produces a portrait of a handsome, broad-faced Black man in work clothes and a well-worn hat.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2e/2a/2e2ac4d4-e201-4b81-a657-c8e8b17c3d15/julaug2022_c03_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

The Magnolia Plantation, near Natchitoches, Louisiana, enslaved as many as 275 Black people, who lived in cabins they were forced to build.

Scott Dalton

Cardenas stares at the photograph, wishing she knew more about this man, who escaped bondage by fleeing south through Texas yet did not take the final step of crossing the river. “I don’t have his name, but my grandmother told me this man stayed here and married into one of the local Hispanic families,” she says. “He took a Hispanic last name and his children grew up speaking Spanish.”

She doesn’t know how many runaway slaves passed through the Jackson Ranch on their way to Mexico, but from her grandmother’s stories she estimates several dozen at least and perhaps a hundred. “Dozens more stayed and married into local families,” she says. “Not everyone wants to admit it, but there’s a lot of African blood around here, and most of it came from the runaway slaves who stayed.”

A few miles downriver, in another small family cemetery, two women tell the story of a white man named John Webber. “He came to Mexican Texas as a single man and settled near Austin in Webber’s Prairie, which later became Webberville,” says Roseann Bacha-Garza, a historian. “He fell in love with his neighbor’s slave, Silvia Hector, and had children with her. He emancipated her in 1834, married her, and purchased the freedom of their children.”

After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 passed, Webber moved his family to the lower Rio Grande Valley, and bought 8,856 acres of land in 1853. “Like the Jackson Ranch, it became a stopping place for runaway slaves going to Mexico,” says Sofia Bravo, a direct descendant of Webber and Hector’s. Bacha-Garza adds, “John and Silvia built a ferry landing and licensed a ferry that went across to the Mexican side of the Rio Grande. It was useful for his business—he was a trader—and also for ferrying runaways.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/36/35/36355da3-6944-459b-9f41-296a1ff41110/julaug2022_c07_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

Sofia Bravo, a descendant of John Webber and Silvia Hector, the formerly enslaved Black woman he married. Webber, Bravo says, “was known here as Juan Fernando.”

Scott Dalton

“I’m very proud of my great-great-grandfather,” says Bravo. “It took guts to marry a Black woman and bring her here. He provided for her and her children, and he didn’t care what race you are.” Glancing around the muddy cemetery at the graves of her ancestors, who include Caucasian Spaniards, African Americans and Indigenous Mexicans, she adds, “I’m the same way. We all fit in the same-size hole when we’re dead.”

Recommended Videos

[ad_2]

Source link