[ad_1]

When Donald Trump started a trade war with China in 2018, Mexico looked well placed to benefit.

For American manufacturers scrambling to dodge newly imposed tariffs on Chinese imports, the attraction of moving production to their southern neighbour seemed clear. Mexico offered a skilled workforce, good road and rail connections, an established export industry and privileged trade access.

The stage appeared to be set for a boom in “nearshoring” — relocating production closer to home. A bonanza beckoned, perhaps rivalling the one Mexico enjoyed in 1994 after the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

It didn’t happen. Between 2018 and 2021 the proportion of manufactured goods imported into the US from Mexico barely changed according to data compiled by Kearney, the consultancy. Instead the rewards of the China boycott were reaped by low-cost Asian competitors including Vietnam and Taiwan. Asian countries other than China increased their share of US manufactured goods imports from 12.6 per cent to 17.4 per cent over the period.

The rapid growth in total US goods imports from Mexico that might have been expected had nearshoring taken off was also missing. It rose by just 11.8 per cent over three years to $384.6bn in 2021, according to the US Census Bureau — after allowing for inflation the total increase was just under 4 per cent.

“Most of the gains have gone to Asean, India and Korea,” said UBS in a recent report examining nearshoring in Mexico. “At least for now, the US import penetration data does not support the view that Mexico has been a net beneficiary of nearshoring.”

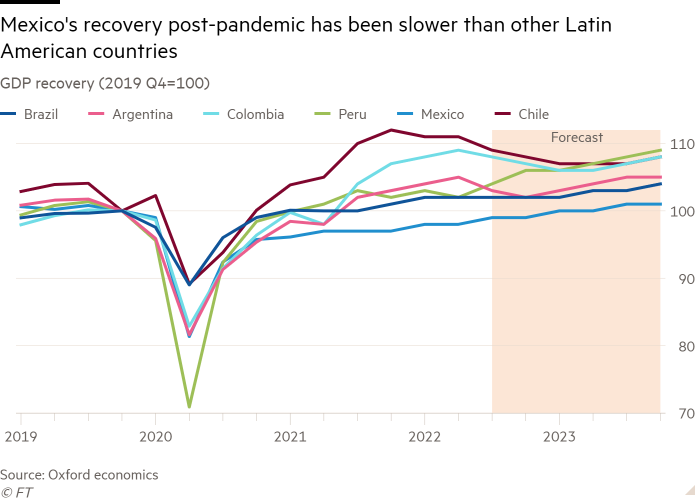

There have been some signs of increased activity. Mexico attracted $34.9bn in foreign direct investment in the year to the end of March, up from $26.1bn a year earlier — although that figure includes large one-off transactions outside the manufacturing sector. Industrial parks in the north of the country are full and some international companies have relocated there. But despite this, Mexico’s overall economic growth over the past three years has been among the weakest of Latin America’s larger economies.

“This should be the golden era for investment in Mexico,” says Mauricio Claver-Carone, president of the Inter-American Development Bank and a big supporter of nearshoring. Calculations by the IDB suggest Mexico has the potential to deliver almost half of the $78bn in additional annual exports from nearshoring that the bank estimates Latin America could generate in the medium term.

Claver-Carone says there is plenty of interest from executives in moving to Mexico: “Not a day goes by without a major company calling me up and saying, ‘Hey, we want to invest [in moving production], can you help us in Mexico?’”

Yet the interest has not yet translated into measurable economic gains, says Ernesto Revilla, head of Latin America economics at Citi and a former Mexican finance ministry official. While nearshoring has become a buzzword in discussions about the future of the Mexican economy, he says, “nobody knows how to continue the conversation”.

The ‘moral economy’

Much of the blame for Mexico’s lacklustre economic performance has fallen on the shoulders of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Business leaders, diplomats and investors say he has been hostile to some foreign companies and complain that his capricious decision-making and authoritarian tendencies are scaring off investment.

López Obrador came to power in 2018 on a leftist, nationalist platform. He dreams of restoring Mexico’s economy to the oil-powered, state-dominated days of the 1970s. His quixotic pledge of a “fourth transformation” of the country — a change he puts on a par with Mexico gaining independence from Spain — promises to eliminate corruption and speed up growth. He wants to create a “moral economy” that puts the poor first, but his regular naming and shaming of multinationals at daily news conferences does little to instil confidence in foreign businesses contemplating forays into Mexico.

Despite his heavy criticism of low growth under previous “neoliberal” governments, in the first three full years of his own administration Mexico’s gross domestic product contracted overall. It is the only major Latin American economy whose output will still be below pre-pandemic levels by the end of this year, according to estimates from JPMorgan.

Mexico’s poor performance is “a direct consequence of . . . Amlo-nomics, which is extremely tight macroeconomic policy coupled with very bad microeconomics,” says Citi’s Revilla, using the acronym that has become the president’s nickname. “The result is not surprising: it’s very low growth.”

Andrés Rozental, a former deputy foreign minister who now works as a consultant, agrees. “We had everything to gain from the global geopolitical situation,” he says. “But it’s all been squandered because of López Obrador’s anti-private sector policies.”

The president’s obsession with “republican austerity” — he flies economy class and took a large personal pay cut — has meant salary reductions for top officials. This in turn has led to a brain drain, budget cuts at government agencies and sharply reduced spending on infrastructure.

Mexico has the lowest public investment among OECD countries, spending just 1.3 per cent of GDP in 2019, the first year of López Obrador’s government. Much of what remains is channelled into a handful of grandiose projects championed by the president. The most prominent is a new oil refinery in his home state of Tabasco, whose cost has spiralled to between $16bn and $18bn, according to Bloomberg.

López Obrador has repeatedly attacked Mexico’s autonomous regulatory agencies, criticising their decisions, cutting budgets and suggesting that they collude corruptly with business.

“Mexico has a big comparative advantage in farming but there are problems in [agricultural health agency] Senasica,” says Luis de la Calle, an economist who runs a consulting firm in Mexico City. “We are a big exporter of fish and seafood, but the government took away funding from [fishing council] Conapesca. We are a big exporter of medical equipment but they cut money for the certifying body Cofepris. It’s madness.”

One of López Obrador’s first decisions as president was to shut the government agency ProMéxico, which worked to promote investment in Mexico and had 51 offices overseas. The president said they were “supposedly dedicated to promoting the country, which is ridiculous because there are no ProGermany, ProFrance or ProCanada offices”. In fact, most countries have government agencies to promote foreign investment.

“Deep down,” de la Calle says, “López Obrador believes that economic success is not possible by itself. It is always the result of luck or corruption.”

Foreign targets

Despite the downbeat mood, the government and some experts insist Mexico could still take advantage of supply chain disruptions caused by Covid-19, higher shipping costs and Ukraine invasion-related fuel price surges that make the economics of moving production to Mexico more compelling.

Tatiana Clouthier, Mexico’s economy minister, argues the country is “doing well for investment” in nearshoring. “It always could be [more] . . . There always could be better circumstances for everything,” she says.

For many years, Clouthier says, Mexico has suffered from “an imbalance, where the thinking was about how to strengthen investment and the social part was ignored”. Now, she says, “the idea is to try to compensate for that”. In practice, the shift in policy has brought decisions that upset foreign companies. Those from the US, Mexico’s biggest foreign investor, have been particularly exposed.

Last month the government forced Vulcan Materials, the biggest American producer of aggregates used in US construction, to halt quarrying in the southeastern state of Quintana Roo, with López Obrador warning that an “ecological catastrophe” was taking place. Vulcan, which has operated in the area for 30 years, has described the shutdown as “arbitrary and illegal” and has sought arbitration under the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement, the successor trade pact to Nafta.

The dispute prompted a letter from a group of US senators last month to President Joe Biden, calling on him to take immediate action to stop Mexico’s “aggression towards US companies”. “If these violations are allowed to continue, they will . . . encourage businesses to seek more predictable and suitable markets elsewhere,” the letter said.

In 2020, Constellation Brands, a large American drinks company that makes Corona beer for the US market, cancelled a $1.4bn factory being built in the northern city of Mexicali after the government revoked its construction permit. The company has since agreed to build a facility in Veracruz but work has yet to start.

Companies from Spain, the former colonial power, have also been targeted. That Spain is Mexico’s second biggest foreign investor after the US cuts little ice. Spanish companies “abused our country and our peoples”, López Obrador told a news conference in February. In a reference to the post-Nafta decades, he added: “During the neoliberal period, Spanish companies supported by the political establishment saw us as a land to be conquered.”

A particular target of the president’s ire has been Iberdrola, the Spanish power company that owns a string of electricity generating plants in Mexico. He has accused it of corrupt deals, something Iberdrola denies. Iberdrola had announced plans to invest $5bn in renewable energy projects in Mexico during López Obrador’s term but has now abandoned almost all of its Mexican investment and is fighting the government in the courts.

The attacks on Iberdrola are part of López Obrador’s crusade to restore the state to pride of place in Mexico’s energy sector. Previous governments had chipped away at the state’s historic monopoly over energy, allowing the private sector to operate electricity generating plants serving industrial customers in the wake of Nafta.

A landmark 2013 constitutional reform opened up the oil, gas and electricity sectors more widely but, since he took power, López Obrador has opposed these reforms and launched a wave of initiatives to roll them back. These include a law changing Mexico’s electricity grid rules to favour the fossil fuel-heavy state power generator, CFE, at the expense of private companies.

As foreign power generators fight the government in the courts, companies that need power for new plants in Mexico are struggling to secure adequate supplies. Worse, the CFE’s reliance on CO₂-emitting oil and gas plants rules it out for multinationals which are committed to reaching net zero carbon emissions targets.

Alberto de la Fuente, president of Mexico’s Executive Council of Global Companies, which represents 57 multinationals accounting for 40 per cent of foreign direct investment, has warned that if Mexico cannot fulfil its clean energy goals, companies “will simply leave”.

Behind closed doors

While foreign companies have borne the brunt of López Obrador’s attacks, the handful of big Mexican businesses that control large parts of the economy have been less affected.

When the president wanted to tackle inflation, his government invited Mexican business leaders for private conversations to agree an informal pact limiting price rises on basic groceries. “It wasn’t a big sacrifice,” noted the owner of one large Mexican group.

Mexico’s oligarchs have reinforced the impression of a cosy relationship with the president by making supportive statements in public and confining any criticism to conversations behind closed doors. “All the Mexican business leaders complain about Amlo,” says the chief executive of one big foreign company. “But when they meet him, they all appear afterwards in public saying how wonderful he is . . It’s a circle of collusion.”

López Obrador has also made life difficult for international businesses in Mexico in less direct ways. Shortly after taking office, he cancelled a $13bn new airport for Mexico City that would have replaced the congested Benito Juárez facility, claiming the partly-executed project was too extravagant, even though cancelling it cost billions.

“The airport decision was 100 per cent political,” says one leading Mexican businessman. “It was the worst economic decision this government has made.”

Instead, López Obrador ordered the army to remodel a nearby military air base and turn it into an additional airport for the capital. The new Felipe Ángeles facility opened in March at a cost estimated by former finance minister Carlos Urzúa of $5.7bn. Most airlines have shunned it because of its poor road and rail connections (the government is working on new transport links). Its only regular international flight goes to Venezuela, a nation under US sanctions. Flights to Cuba, another nation under US sanctions, are due to start in July.

The new airport is only 45km from Benito Juárez, a proximity that has forced a controversial redesign of Mexico City’s airspace. This triggered what the International Air Transport Association called a “very worrying” increase in alerts over flights at risk of collision. Mexico’s airlines are currently unable to expand flights to the US because the Federation Aviation Administration downgraded its air safety rating last year.

“We are losing out on the potential we have as a country and as a city” because of the airport situation, says the chief executive of the foreign firm. “There may come a moment where you have to fly to Monterrey to take a plane to Barcelona.”

Despite this, Omar Troncoso, a nearshoring expert at Kearney in Mexico, sees some reason for optimism in the recent geopolitical shifts. He said that as recently as last year, “Mexico was still more expensive than many [Asian] low-cost countries” when total costs of getting the product to the customer were factored in. Then “we had a massive disruption in [the] supply chain and . . . the price of a container being brought from China to the US skyrocketed . . . It [is] now cheaper to produce in Mexico,” he says.

Troncoso believes that the nearshoring aimed at supplying the US market currently under way will take another two or three years to show up in the data. “If you . . . look for a space in some of the border cities . . . the real estate agents will tell you that you’re going to have to wait until 2025 — everything . . . is already sold out.”

Sergio Argüelles González, head of Mexico’s industrial parks association, says 2021 was a bumper year with “spectacular demand” and predicts this will continue if there are sufficient power supplies.

“In spite of Amlo, something is happening,” says Citi’s Revilla. “The [momentum] for nearshoring is big and hopefully will outlast Amlo and help Mexico in the medium term.” De la Calle, the consultant, voices a similar view: “Nearshoring is happening,” he says. “But . . . if we did things properly, it could be three times more than it is now . . . The opportunity cost of López Obrador is very big.”

[ad_2]

Source link