[ad_1]

This photo shows the launch of Ocean Era’s Velella Beta-test, with the S.S. Machias as the tender to the net pen.

PHOTO PROVIDED BY OCEAN ERA INC.

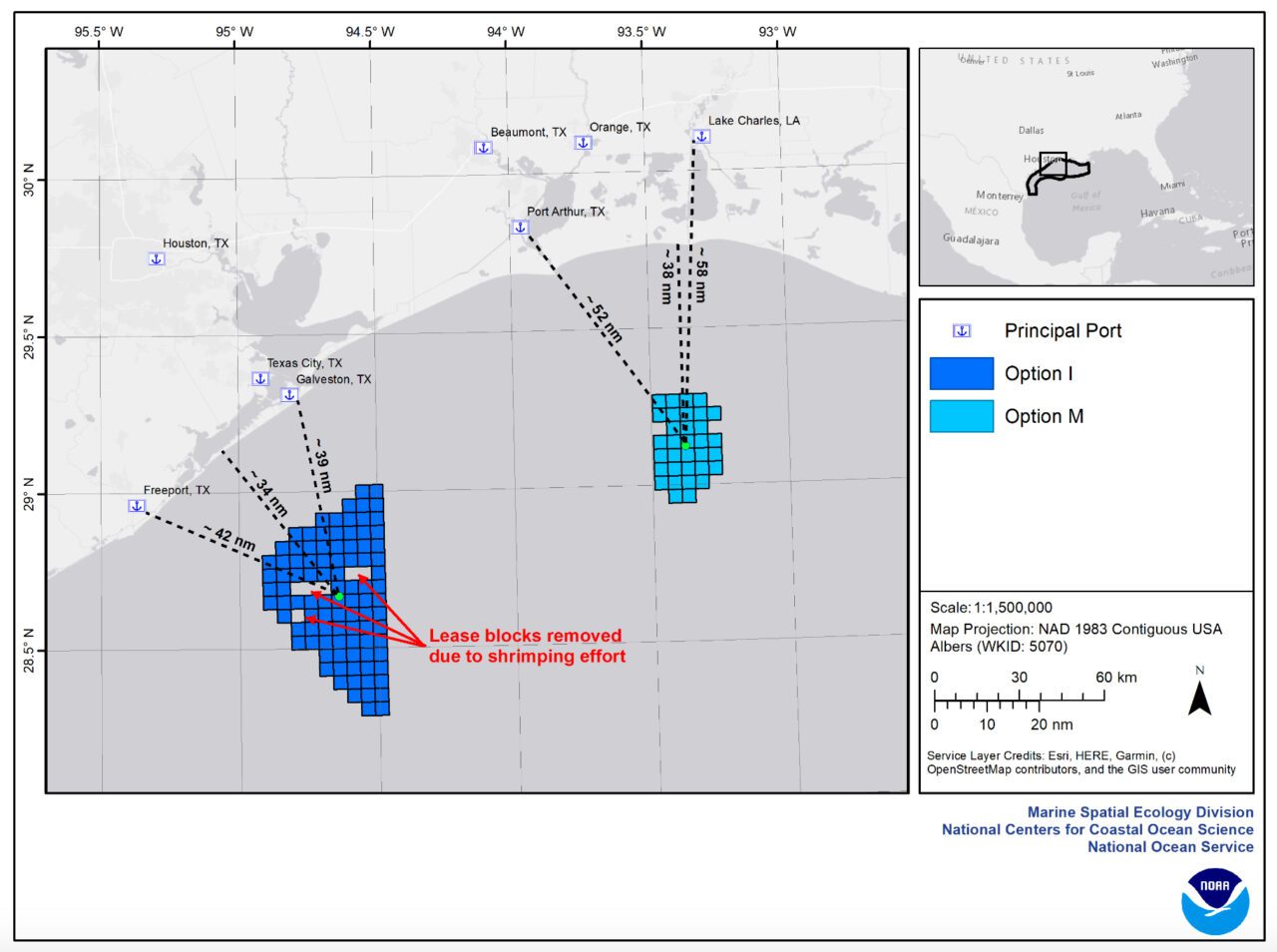

VENICE — Velella Epsilon, a fish-farming demonstration project proposed for the Gulf of Mexico about 45 miles off the coast of Venice, has received its National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit in spite of opposition from environmental groups that allege it could have adverse impacts on water quality and sea life.

The permit goes into effect July 8 and is good for five years. Opponents are discussing whether to file suit to challenge it.

A lawsuit wouldn’t hold the project up, said Neil Sims, founder and CEO of Ocean Era Inc., the company behind it.

“We have the permit and we can move forward,” he said, adding that one more permit, from the Army Corps of Engineers, is still needed.

The net pen the fish will be farmed in needs to be installed by the first quarter of next year, he said.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s issuance of the permit is the culmination of a nearly four-year process in the approval of the project, which proposes to raise 20,000 food fish over the course of a year with an estimated 85% to 90% survival rate.

During that time, it’s estimated the fish would grow to an average of 4.4 pounds each.

The project was required to get an NPDES permit because the excess fish food and the fish waste it will discharge contain pollutants — which is one of the reasons it attracted opposition.

But the Final Environmental Assessment for the project, issued in September 2020, concluded that the discharges “are expected to have unavoidable minor impacts, primarily in the immediate vicinity of the proposed project.

“For the most part, these impacts would be short-term in nature, limited in spatial extent, and expected to have a low likelihood to result in cumulative impacts.”

As part of receiving the NPDES permit, Ocean Era is required to report regularly on its efforts to minimize the negative impacts of the farm.

Studies of similar operations show that if the pens are sited deep enough and where there are steady, strong currents, there are no significant impacts to water quality or the substrate, and often no impacts, Sims said.

That’s been the case with the company’s two prior demonstration projects, he said.

The first, Velella Beta, was a free-floating net pen near the company’s headquarters in Hawaii. A ship kept the pen in a designated area.

The pen, which was in place for eight months and raised 2,000 fish, became a popular spot for divers and anglers, he said. If it had done any damage to a nearby coral reef, divers would have been “kicking and screaming.”

The second, Velella Gamma, was also a net pen, but this time anchored in 6,000 feet of water with a 15,000-foot tether. It, too, raised 2,000 fish over eight months.

“The local community loved it,” he said, in part because it brought other fish to the area.

‘Other people’s lunches’

Originally named Kampachi Farms, Ocean Era was founded to develop environmentally friendly methods of aquaculture, Sims said, because it was apparent that the protein needs of the planet’s population couldn’t be met by traditional sources, and that they posed environmental problems.

That was particularly true in the U.S., he said, because the country imports more than 90% of the fish it consumes while farming none in the open waters of the world’s second-largest exclusive economic zone.

“That’s immoral,” he said. “We cannot continue to eat other people’s lunches.”

“Kampachi” is the Japanese name for almaco jack (Seriola rivoliana) — the fish raised in the Velella projects. It’s native to the Gulf, and the “fingerlings” will come from Mote Marine Aquaculture Research Park.

The farm will be a copper-alloy pen about 20 feet high and 50 feet across. It’s to be tethered in water about 130 feet deep and can operate on the surface or be submerged in stormy weather, with its position marked by a buoy, according to an EPA fact sheet.

A ship would deliver up to 28,000 pounds of food a month.

The Gulf is the site for Epsilon because the almaco jack — also known as longfin amberjack — are native. The fact the Gulf is more shallow than the open ocean actually works against the project because he’d prefer to anchor the net pen deeper, Sims said.

But because it’s a demonstration project, he said he also wants it to be accessible to the public so they can see “this is just fish in the water.”

A diver inspects the net pen in the Velella Beta-test.

The cost will be more than $1.5 million, he said, with some of the money coming from the federal government and some from supporters of the project.

“This is not a profit-making operation,” he said.

A commercial fish-farming operation would probably have 10 net pens of 200,000 fish each, he said.

If Epsilon is a success, the next step for Ocean Era would be to apply for permits for a commercial farm. The Gulf would be a potential site for that, too, he said.

Opponents of the project may have a say in that. Federal law gives them 120 days from July 8, the permit issuance date, in which to appeal the decision to federal circuit court.

Members of Don’t Cage Our Oceans, a coalition of organizations fighting offshore finfish farming, and this project in particular, have filed a notice of intent to sue but haven’t decided whether to follow through with legal action, said Marianne Cufone, executive director of Recirculating Farms Coalition.

Her group promotes community-based food production.

Offshore finfish farms have been in operation around the world for years, Cufone said, “with a lot of problems.”

Fish are selected for farming because they have attributes conducive to rapid growth. If they escape, they can outcompete wild fish for food because they’re bigger. But they’re not necessarily as well equipped to survive in the wild, she said.

And interbreeding can cause “genetic pollution,” weakening wild fish populations.

Then there are the potential environmental impacts from anything that comes out of the cage: food, fish waste, antibiotics and other chemicals, she said.

“It all goes somewhere,” she said.

All of them could have a harmful impact on communities whose economies — tourism, commercial and recreational fishing, other marine-related businesses — depend on a healthy coast and clean water, Cufone said.

She criticized the review the project received, saying, “I’m not sure that the agencies did a deep-enough dive.”

The environmental assessment was superficial because it glossed over the chemicals and antibiotics the fish will receive; what will be done with sick fish; how any potential cleanup will be paid for; and how well the cage will ride out a hurricane.

“I have seen whole oil platforms brought to shore,” to avoid one, said Cufone, who’s based in Louisiana.

Glenn Compton, of the environmental group ManaSota-88, said such fish farming is another reason for Floridians to be concerned about water quality.

Velella Epsilon’s permit is for open discharge, he said, meaning the wind and currents will direct where anything coming out of the cage goes, with very little chance to monitor it.

“The real concern is that the Gulf of Mexico is already under significant stress from pollution,” he said.

Yet the gulf seems to be a favored area for fish farming projects, he said, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration considering allowing commercial aquaculture off of Collier and Pinellas counties, as well.

Fish farming can’t be made safer for the environment off the state’s coast, Compton said.

“There’s really no mitigation,” he said, “You’re either going to approve these things or you’re not.

Sims said that critics are ignoring the science, which has caused some environmental groups to warm up to the concept of open-water fish farming.

He named the World Wildlife Fund, The Nature Conservancy Conservation International and the Environmental Defense Fund as organizations that see its potential, if properly located.

Concerns about fish escaping from the pen are “irresponsible,” he said.

They will be the unaltered progeny of native fish, he said, and any that manage to get out will be “bait more than anything else,” poorly equipped to survive in the wild.

Opponents of the project “just don’t like the idea of companies doing business in the ocean,” Sims said. “I’m sorry, but we need to.

“When done right, it’s a beautiful thing.”

[ad_2]

Source link