[ad_1]

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column by Eduardo Prud’homme as part of a regular series on understanding this process.

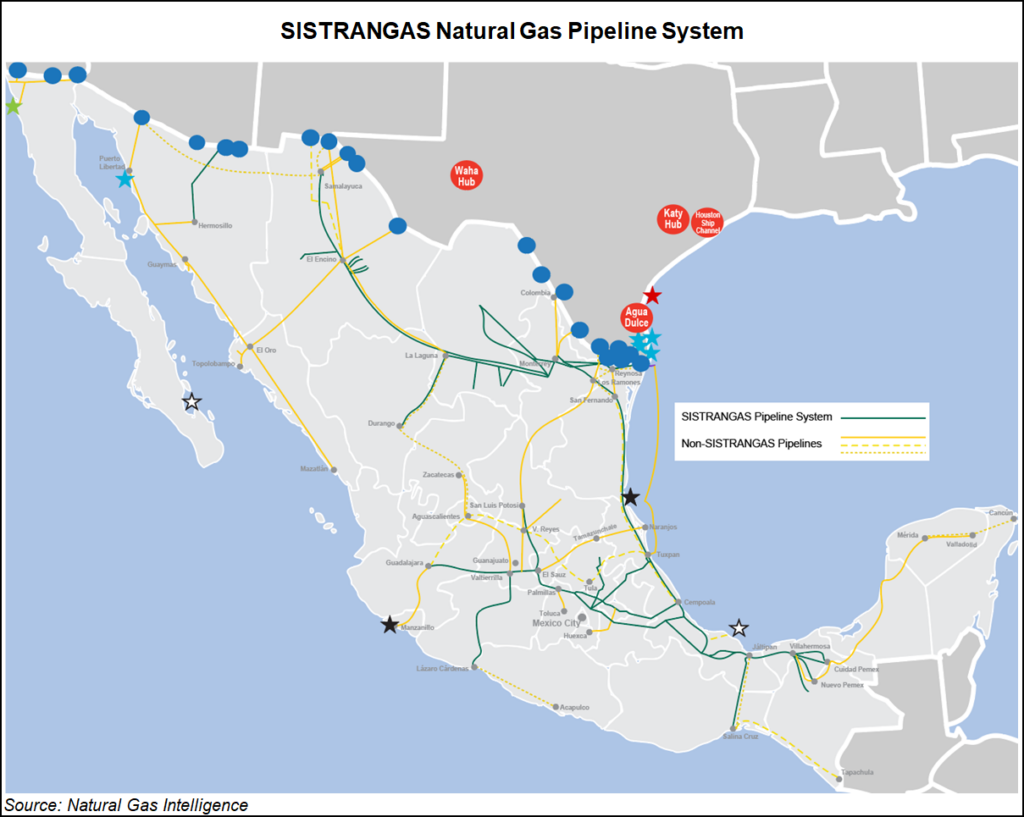

The spring of 2017 promised a change in the natural gas industry in Mexico. An open season to allocate capacity on the Sistrangas national pipeline system, together with an auction of capacity in the main gas entry pipeline into the country, paved the way for private traders to offer supply proposals to Mexican consumers. At the time, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) was barely able to meet half of national demand through its production. Energy regulator Comisión Reguladora de Energía (CRE) and Energy Ministry Sener knew that depending on Pemex as the only intermediary capable of importing gas was not the best practice to benefit users.

Although the legal framework was one of total openness, the challenge to developing a competitive gas market had to do with reputation. External agents had to be convinced that they would be treated fairly. The solution was the creation of Cenagas, an independent organization that would manage Sistrangas.

The fact remained that Cenagas was also a Mexican state company – that is, a related party of Pemex and the Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE). For this reason, a clear mandate of impartiality and independence had to be included in the law. That is why capacity management in the Sistrangas is regulated by the CRE and must be carried out in strict adherence to open access obligations. If Cenagas does not guarantee effective open access and is not unduly discriminatory, its very existence has no meaning.

Five years after the creation of Cenagas, users in Mexico can still choose their supplier. The separation of activities and the effectiveness of transportation contracts on a firm basis allows a company like BP Energy to reserve 184,187 GJ/d of capacity on the network. Many other Mexican and international private trading companies compete in the market, adding up to an energy equivalent of 1.3 Bcf/d. This volume, very significant given the size of the Mexican market, shows that wholesale gas buyers do not always choose Pemex if they have options – nor do they choose CFE.

CFE obtained a good part of the transportation capacity offered by Sistrangas because the Hydrocarbons Law took into account its generation capacity and deemed it of national interest. At the time of allocating capacity, CFE was the first on the list to choose routes and quantities. However, positions had to be linked to the consumption of its generation plants or independent power producers dedicated to delivering energy. CFE and its commercial subsidiaries have under contract a maximum daily aggregate amount with Cenagas of close to 1.91 million GJ/d. This volume already exceeds the total of all trading companies in Mexico. In addition, other users have given CFE capacity in Sistrangas so that it can manage it as part of their supply agreements. At least another 70 MMcf/d is used to deliver gas to third parties. In short, CFE moves more than 2 Bcf/d on the Sistrangas.

In the past few days, a document sent by Sener to Cenagas and CREmade clear its position regarding open access and the promotion of competition. Despite going against the principles of open access as enshrined in the law, Sener wants users of the Sistrangas to buy gas exclusively from Mexican state companies. If the plan were to be enacted, users would be given 60 days to comply.

If there is a dilemma between buying gas from Pemex or CFE, the latter should prevail, the document stated. Sener said CRE should change the rules and conditions of service to take this into account.

This administrative act could have major implications. Commercialization by private parties will be made difficult by always having to include the intermediation of CFE.

The arguments contained in the official letter do not justify or motivate the actions of Sener. Any enactment of this strategy would be illegal, and therefore could be challenged in court. However, the most serious thing is that it exhibits the intellectual poverty with which energy policy is being designed. The government sees the capacity that CFE has in the Sistrangas as a problem. However, what the market is anxiously demanding is an open season that allows a new allocation of maximum daily quantities in primary points to improve supply reliability.

The Sener strategy goes against all standards of free competition. It clearly defies international treaties such as the United States-Mexico-Canada-Agreement, or USMCA. Open access is a necessary condition to achieve a diversification of supply sources and for efficient market development. If there is no open access, daily operations are concentrated on the decisions of fewer agents and thus the continuity of services is at risk. Being under the power of public companies with technical deficiencies and legal limitations to carry out risk transactions, the reliability of the services is subject to bureaucratic decisions.

Cenagas has the legal mandate to operate independently of any market agent. This independence was taken care of in its institutional design by preventing it from executing commercialization activities and avoiding operation conflicts in the order dispatch. The nominations it manages must be treated impartially and under technical criteria. You are expressly prohibited from favoring any of your users over others.

June is the month in which the renewal of transportation contracts between Cenagas and Sistrangas users takes place. This process has not followed the practices of recent years and will most likely be conditional on compliance with Sener’s instructions. This type of coercive action has already been exercised by Cenagas, such as was seen in the case of the Braskem contract. Once this company agreed to negotiate with Pemex, its transportation contract was reinstalled.

Given the risk of seeing their supply interrupted, users will hardly take legal action to maintain their gas acquisition alternatives and will prefer to accept this condition. With this minor administrative measure, there is a scenario in which the events correspond to a regression to the world of a single supplier that Mexico had in 2014. With the support of Sener, CFE will be able to exercise market power. Unlike Pemex, CFE and its subsidiaries are not agents subject to any economic regulation. The consequences go beyond the Sistrangas. A de facto elimination of the possibilities of competition in the sale of gas gives CFE market power in the electricity generation industry too. CFE will have a direct influence on the way its competitors obtain their fuels. This condition of monopoly in the Mexican market in the sale of energy in the gas sector is more concentrated and powerful than Pemex ever had. The gas sales regime by Pemex was always regulated by the CRE. On the other hand, CFE does not have to respond to any authority regarding gas. This administrative decision occurs at a time of the most volatility in the gas market recorded in the last two decades. The way to counteract the effects of these price variations is through financial instruments that can only achieve the necessary liquidity when they are associated with a market with good logistical conditions and with a significant number of participants involved in gas transactions. The concentration and control of the market by CFE violates energy security and affects the country’s competitiveness. Perhaps we are about to say goodbye to the possibilities of having a modern gas market. Let’s hope that’s not the case.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO chief officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas). Based in Mexico City, he is the head of Mexico energy consultancy Gadex.

[ad_2]

Source link