[ad_1]

On June 25, 1983, two distinct marches set out from Mexico City’s Monumento a Los Niños Héroes. One was a traditional march, with a serious tone in line with the established patterns for Mexican leftist marches. The other included not only queer Mexicans but also sex workers and punk-like chavos banda, who laughed, danced, and wreaked fun havoc—or, in Mexican parlance, engaged in desmadre. This second march also included a stop at the U.S. Embassy to burn Ronald Reagan in effigy to protest U.S. interventions in Central America.

The two contingents were at odds. In 1984, they even came to blows, pushing and shoving each other at the marches’ end point, the Hemiciclo a Benito Juárez.

Many contemporary queer Mexicans don’t know this history, yet it is more important than ever today. In 1983, queer Mexicans faced turbulent times, grappling with the effects of the crushing 1982 debt crisis, early news of the AIDS epidemic, and fallout from U.S. interventionism in Central America. Today, queer people face a parallel conjuncture: economic recession, contentious politics, and a War on Drugs that has increased violence against women and LGBTQ Mexicans, and now COVID-19.

In both historical moments, economic and political crises fractured the queer community. Why? Because queer activists are shaped by class and other factors. Around the world, they wrestle with economics, politics, and with what those things have to do with sexual and gender identity. When economic crises accentuate class-based tensions, it plays out as conflict over how to be queer and how to fight for queer liberation.

As in many other parts of the world, publicly visible queer activism in Mexico began in the 1970s. While same-sex acts had been technically legal in Mexico since the late 19th century, individuals who identified as jotos, vestidas, lesbianas, homosexuales, travestis, mujercitos, and bisexuales (terms that refer to people who engaged in same-sex acts and/or questioned gender expectations, and do not map perfectly to today’s LGBTQ categories in the United States) faced ostracization from family and friends and harassment, arrest, and extortion by police via public decency laws.

In the face of this, Mexico City queers of the mid-20th century created class-based, largely hidden social lives. Wealthy gays gathered in private homes or in clubs with expensive entry fees. Some searched out hookups with poor gay men in bars or on street corners, slumming in what they called the “guetos lumpen” or “lumpen ghettos.” Poor homosexuales, especially the vestidas or cross-dressing men, engaged in sex work.

Though “hidden,” these queer social spaces were never fully out of sight—interested people could go to the right public spaces, department stores, restaurants, and clubs, look the part, and ask the right questions to find others like them. The Mexico City police knew where to find them too, and subjected gay and/or cross-dressing men to verbal harassment and razzias (raids) at bars. Murders in the community went uninvestigated.

It’s important to remember that the queer movement emerged out of precisely these coalitions—solidarity between middle-class and working-class queer activists and with other groups fighting for liberation such as workers, immigrants, and oppressed racial groups.

So, in the early 1970s, inspired by the 1968 student movement as well as the recent rises of feminism, anti-imperialism, and the civil rights movement, Mexico City’s queer people began to organize. But just as past gay social life had been class-stratified, so was early organizing. Cosmopolitan middle- and upper-class queers traveled to New York City in 1969 in the wake of the Stonewall Riots and to Europe to meet members of the French front homosexuel d’action révolutionnaire. Inspired, they returned to Mexico and formed the Frente de Liberación Homosexual de México (Homosexual Liberation Front of Mexico, or FLH).

The FLH operated within the confines of homes, largely in the form of reading groups. Many knew from experience in other kinds of political organizing that the police and military often targeted activists to squash dissent. Some worried further that taking their queer activism public would alienate them from their comrades in other activist circles, who often saw homosexuality as irrelevant to political organizing—or worse, bourgeois and anti-revolutionary.

Eventually, a group of frustrated ex-FLH members got fed up with secrecy. In 1978, they branched off to create the Frente Homosexual de Acción Revolucionaria (The Homosexual Front of Revolutionary Action, FHAR) and joined a march celebrating the Cuban Revolution—marking the first time an openly queer contingent marched for change on Mexico City streets. The following year FHAR joined forces with Lambda, a Trotskyist gay liberation group, and the lesbian-feminist Oikabeth to organize Mexico City’s first marcha de orgullo homosexual—or gay pride march.

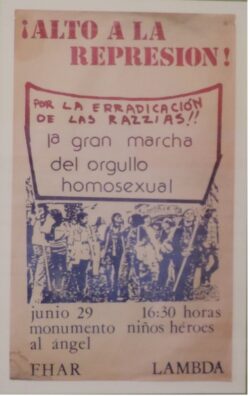

Poster from the First Marcha de Orgullo Homosexual. Courtesy of Colectivo Sol.

At first, the three groups worked together to push back against police raids. They wrote letters to officials and op-eds to counter criminalizing and negative portrayals of queer individuals, and they talked with newspaper reporters about using respectful terminology. They marched to uphold their constitutional rights to expression and assembly. They also collaborated with activists demanding justice for the desaparecidos (the hundreds of activists and allies kidnapped, tortured, and secretly incarcerated or murdered during the Mexican government’s Dirty War from 1964 to 1982). The activists’ queer identities intersected with their activities as unionized laborers, student activists, party militants, and members of other political organizations.

Yet as the economy plummeted in the early 1980s, class-based tensions surfaced. The activists argued about the meaning of homosexuality, the role of travestis (cross dressers) in the movement, the appropriation of homophobic slurs, and how best to present their movement in the world and demand respect for their rights. When middle-class LAMBDA ran candidates for legislative bodies, others critiqued them as assimilationist. When working-class-aligned activists—whose coalitions included sex workers and chavos banda—appropriated slurs and expressed their queerness flamboyantly, they put themselves at odds with lesbian groups, who argued that cross-dressing gay men and transvestites made a ridicule of cis-women. These tensions divided the march into two fractions.

Debates over assimilation and respectability still haunt queer organizations. Today, there remains a divide over capitalism, assimilation, and “selling out” at Mexican Pride. Mexico City hosts two Pride marches. The first is larger, and the kind you see around the world: filled with floats sponsored by LGBTQ organizations, NGOs, government offices, and multi-national companies such as Visa and General Electric. The second is much smaller, and its participants are leftist queer activists.

The movement is splintered. As in the U.S., the mainstream face of Mexican queer activism focuses on “sexual diversity” and has focused its attention on marriage, representation within government institutions, and the creation of gay-themed consumer products such as Levi’s’ Pride collection. Meanwhile, a smaller group of anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist queer Mexicans organize around ideas of “corporeal and sexual dissidence,” seeking specially to address violence against trans individuals. This violence has been exacerbated by the increasing visibility of separatist feminists, some lesbian, who reject transwomen with a discourse that resembles that of the country’s elite right-wing party. On the surface these can seem like simple disagreements about respectability politics, but as in the 1980s, the factions fall along class politics as many transwomen in vulnerable situations are working-class.

These divisions are not uniquely Mexican. Around the world, many queer activists are tired of the pandering by multi-national corporations who sponsor floats but prop up destructive business and war efforts. These activists reject mainstream Pride and argue for organizing around efforts that prioritize trans individuals and working-class queers.

It’s important to remember that the queer movement emerged out of precisely these coalitions—solidarity between middle-class and working-class queer activists and with other groups fighting for liberation such as workers, immigrants, and oppressed racial groups. In 1979, Mexican queer activists chanted, “Nobody is free until we are all free!” That spirit must animate today’s queer activists.

[ad_2]

Source link