[ad_1]

As Mexican investigators struggle with the so-far inexplicable death of an 18-year-old woman, the odds of an answer are slim: Even nationally significant homicide cases — like nearly all homicide cases in Mexico — tend to wind up as mysterious as the 1975 disappearance of U.S. union boss Jimmy Hoffa.

Poor evidence handling, intentional distortion of investigations, cover-ups, political interests and just plain incompetence often leave the public without complete answers. Surveys by Mexican think tanks say roughly 90% of homicides go unpunished in Mexico.

In the latest case, law student Debanhi Escobar left a taxi in the northern city of Monterrey on April 9 and the taxi driver took a photo of her standing alone on the side of a highway. Her body was found in an underground water tank at a nearby motel on April 21. An autopsy found she had been dead for between five days and two weeks. She had no water in her lungs and the autopsy found she had been alive when she entered the tank, where the water was 3 feet high and the medical examiner said she could have stood up. The cause of death was a blow to the head. Her handbag was found in an adjoining water tank, and her keys and cellphone were found in another. Her disappearance drew national attention. Authorities have made no arrests.

Julio Cesar Aguilar/AFP via Getty Images

Escobar was one of 31 women and girls who have disappeared or been found dead so far this year in the northern state of Nuevo Leon. The number of people listed as currently missing in Mexico stands at nearly 99,000, according to a national register.

Many other notorious cases have gone unsolved — at least in the public’s mind — for years or even decades:

Paulette Gebara, 2010

Ronaldo Schemidt/AFP via Getty Images

Mexico state prosecutor Alberto Bazbaz resigned in 2010 after he announced that following an extensive, nine-day search for Paulette Gebara, the missing 4-year-old’s body had finally been found in her own bed and overlooked by police. Bazbaz claimed Gebara had been accidentally smothered in her own bedding and prosecution agents apparently found her only after the body began to smell. One year later, Bazbaz was appointed as head of the country’s national intelligence agency.

Bradley Will, 2006

Alfredo Estrella/AFP via Getty Images

Bradley Will, 36, an independent U.S. video journalist and activist, was shot to death while accompanying radical activists who took over the southern Mexico city of Oaxaca during massive protests. Authorities quickly charged one of the protesters — not government supporters — with Will’s killing, even though the two sides were clashing when Will was shot. But in 2010, a court dismissed those charges for lack of evidence, and nobody else has ever been brought to justice in the case.

Digna Ochoa, 2001

Carlos Salinas/AFP via Getty Images

Human rights lawyer Digna Ochoa was found dead on the floor of her Mexico City office in 2001, and rights groups suspected her enemies in the army, the government or the timber industry had silenced her. The circumstances were strange. An anonymous note found near her body seemed to threaten other human rights activists. Ochoa had been shot twice with her own pistol and there was no sign of forced entry. Investigators didn’t find any unusual fingerprints and wondered why Ochoa was wearing rubber gloves, and why there was flour sprinkled all over the scene. The chief investigator on the case was forced to resign after he concluded Ochoa shot herself to become a human rights martyr. Nobody has ever been convicted in the case.

Abraham Polo Uscanga, 1995

Sven Kaestner via AP

Abraham Polo Uscanga was a Mexico City judge who claimed to have received threats from government officials after he refused to order the arrest of members of a dissident bus drivers’ union. He was found dead in his office with two bullet wounds to the head. Authorities quickly ruled his death a suicide but the conclusion was widely ridiculed.

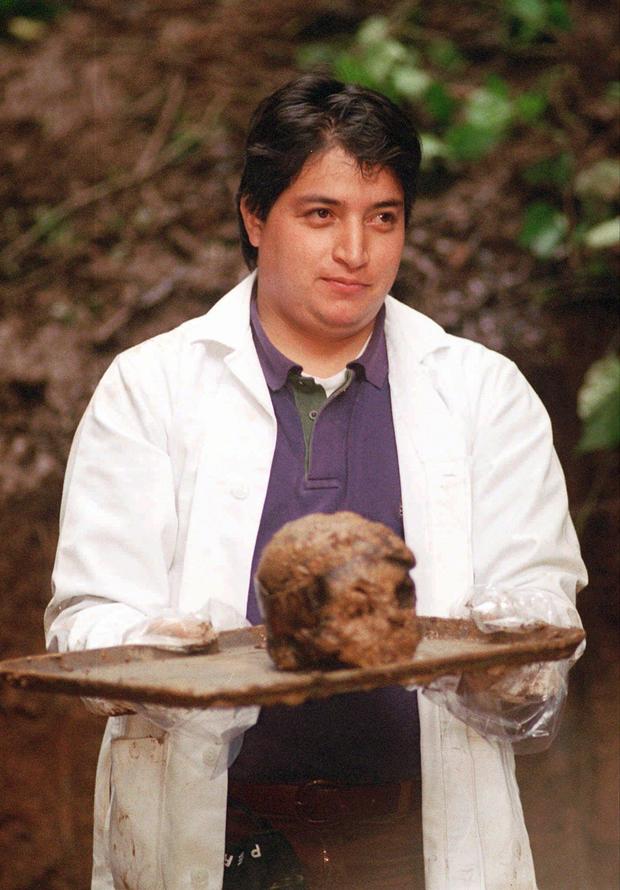

Manuel Muñoz Rocha, 1994

AP

Manuel Muñoz Rocha was accused of helping Salinas mastermind the murder of Ruiz Massieu. A ruling party senator, Munoz Rocha disappeared shortly after the killing and was never captured. In a bizarre turn of events, a federal prosecutor later hired a clairvoyant who led investigators to a skull buried at a ranch owned by Salinas in 1996. But the skull turned out to be from one of the clairvoyant’s deceased relatives and bore the signs of having previously been autopsied. The clairvoyant was jailed for helping plant fake evidence, Muñoz Rocha was never seen again, alive or dead.

Jose Francisco Ruiz Massieu, 1994

Sergio Dorantes/Sygma via Getty Images

Jose Francisco Ruiz Massieu was the leader of the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party. He was shot to death outside a hotel during the hotly contested 1994 presidential campaign. Raul Salinas — Ruiz Massieu’s brother-in-law and the brother of then-president Carlos Salinas — was convicted of ordering the killing. But that conviction was overturned in 2005 and nobody was ever convicted of paying the gunman who pulled the trigger.

Luis Donaldo Colosio, 1994

AP Photo/David Maung

Ruling-party presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio was shot to death at a campaign rally in 1994. Mario Aburto, a 23-year-old factory worker, was detained at the scene and quickly confessed to the shooting, claimed he had acted alone and was sentenced to 45 years. However, Aburto has since complained he was tortured into confessing, and in October the country’s National Human Rights Commission called for his case to be reopened, saying there was evidence to corroborate his claim of torture.

Cardinal Juan Jesus Posadas Ocampo, 1993

Gianni Foggia / AP

Roman Catholic Cardinal Juan Jesus Posadas Ocampo was killed by 14 shots fired at short range on May 24, 1993, while he sat in his car at the airport in the city of Guadalajara. The government said drug cartel gunmen mistook the cardinal’s luxury vehicle for that of a rival drug trafficker. But church authorities believe Posadas Ocampo, who was wearing clerical clothing, was killed because he knew about relationships between drug dealers and government officials. While some of those implicated were charged with weapons or drug offenses and acknowledged participating in the slaying, nobody has ever been convicted for the killing itself.

[ad_2]

Source link