[ad_1]

In late 2017, Mexico made headlines as Italian company Enel bid what was then a world-record low price for renewable energy in the country’s third such energy auction. This development was possible due to the historical and sweeping energy reforms passed with broad support in Mexico in 2013. Then-President Enrique Peña Nieto had succeeded where previous Mexican presidents had failed, reversing decades of resource nationalism and overhauling the energy sector through constitutional reforms that gave the private sector a larger role and advantaged renewable energy in Mexico’s economy. The 2017 auction seemed to indicate Mexico’s bright future not only as a conventional oil producer, but also as a clean energy power.

In late 2017, Mexico made headlines as Italian company Enel bid what was then a world-record low price for renewable energy in the country’s third such energy auction. This development was possible due to the historical and sweeping energy reforms passed with broad support in Mexico in 2013. Then-President Enrique Peña Nieto had succeeded where previous Mexican presidents had failed, reversing decades of resource nationalism and overhauling the energy sector through constitutional reforms that gave the private sector a larger role and advantaged renewable energy in Mexico’s economy. The 2017 auction seemed to indicate Mexico’s bright future not only as a conventional oil producer, but also as a clean energy power.

Just four years later, Mexico and its policymakers are contemplating energy reforms, which would reverse these gains. Mexico’s Congress will soon debate a constitutional amendment supported by current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador that was deemed necessary after Mexican courts challenged the legitimacy of earlier legislation. The president is seeking to restore the dominance of the state in Mexico’s energy sector and, in his view, minimize corruption and level the playing field between the state and private companies. The proposed constitutional amendment would shift control of the power sector back to the state-run utility, the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE), and move now-independent energy regulators back under the auspices of the state. Under the new rules, CFE would have at least 54 percent of the power market and would no longer have to dispatch the lowest cost power first, but instead would prioritize its own power generation. These changes are proposed in the context of a broader push to favor state-run companies, including Mexico’s oil behemoth Pemex, in the energy sector.

The proposed energy reforms would be a significant setback to the aspirations of the agreement and entail opportunity costs to all.

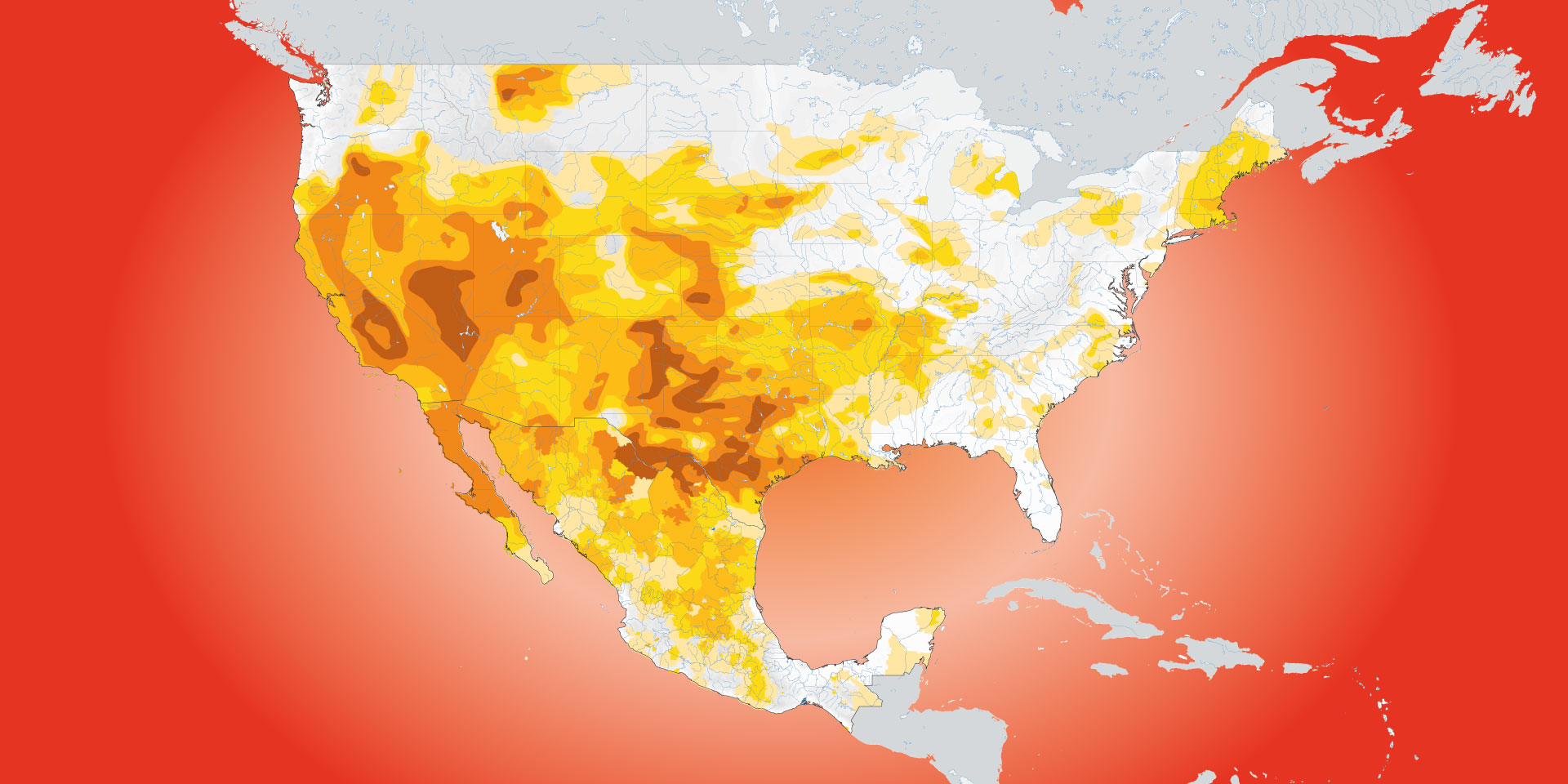

The implications of this constitutional “counter reform,” if successful, are serious and wide-ranging – and go well beyond Mexico’s domestic arena. First, such changes would destabilize Mexico’s renewable energy sector and the ability of Mexico to meet its already too-modest climate goals. The prioritization of power produced by CFE over that of private companies is effectively a move to favor fossil fuels over renewable energy. CFE primarily generates power from hydro, nuclear, natural gas, and fuel oil. Most of Mexico’s green power is produced by the private sector, which means that it would be dispatched last, despite being cheaper. The prospects of Mexico meeting its climate targets – which the Obrador government declined to revise to be more ambitious at Glasgow – would move from dim to nil as renewable energy suffered this major setback. Mexico’s 2012 General Law on Climate Change currently commits the country to generating at least 35 percent of its power with clean technologies by 2024 and to reduce emissions by 30 percent by 2020 and 50 percent by 2050 when compared to 2000. Yet, a 2021 study done by the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) assessed that similar changes to those being advocated today would increase Mexico’s carbon emissions by 26-65 percent.

The proposed constitutional reform would also harm Mexican competitiveness and economic growth. The surge in wind and solar power generation in Mexico since former President Nieto’s 2013-2014 energy reforms has been a boon to manufacturing given the importance of energy costs to such industries. CFE’s power, which will now be dispatched first, will in most cases be more expensive than the renewable energy generated by the private sector. The same study by the NREL expected a dominant role for CFE in Mexico’s power sector would increase electricity generation costs by 32-54 percent and boost the possibility of power outages by 8-35 percent. Moreover, large companies that have been securing power directly from private power plants—many of them relying on renewable sources—would no longer be able to do so and would be forced to turn to the more expensive, less clean power provided by CFE. Higher cost power would make Mexico far less attractive to companies and investors looking for a competitive alternative to basing operations in China amidst increasing tensions between Beijing and the West. Moreover, international companies committed to their own “net-zero” carbon goals would be less interested in establishing operations in a place that would worsen or not improve their carbon footprints.

Finally, the proposed constitutional reforms are almost certain to create greater friction in Mexico’s relationship with the U.S. and Canada. Most significantly, they are viewed by some to be in violation of the USMCA, in which signatories committed not to favor domestic companies at the expense of foreign investors. The trade pact provides remedies to foreign energy investors in Mexico when fair market competition is undermined; Bloomberg calculates that the reforms would jeopardize more than $22 billion of foreign-owned solar, wind, and other renewable-energy installations. The trade pact does not mention the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change nor the Paris Agreement in the list of agreements to which signatories committed to maintain laws or regulations to fulfill such obligations. But the USMCA does affirm each country’s “commitment to implement the multilateral environmental agreements to which it is a party,” and the reforms would clearly hamper Mexico’s ability to do this. In addition to these potential violations of USMCA, the proposed energy reforms would be a significant setback to the aspirations of the agreement and entail opportunity costs to all by preventing the three countries from deepening their trade and other forms of cooperation related to climate. The vision of the continent being “the most competitive and dynamic region in the world” as articulated by the leaders of the U.S., Canada, and Mexico in 2014 would be hard to realize if Mexico moves determinedly away from the private sector and renewable energy.

The American and Canadian governments have both the grounds and a responsibility to urge Mexican policymakers to oppose this constitutional amendment and the general direction of President Obrador’s energy reforms. The push to restore the primacy of the state and, as a result, the role of fossil fuels in Mexico’s economy has implications for climate, competitiveness, and cooperation that are of direct interest and importance to Mexico’s northern neighbors. Both the Biden and Trudeau governments appear to have made this clear to the Obrador administration. Now that the action is shifting to the Mexican Congress with an April 2022 debate and vote looming, so too should the diplomacy of Washington and Ottawa. The implications for the continent’s prosperity, competitiveness, and climate are all at stake.

[ad_2]

Source link