[ad_1]

The world’s first atomic bomb was detonated at a test site in the southern New Mexico desert during the summer of 1945, sending a multi-hued cloud thousands of feet in the air and carving out a crater in the earth a half-mile wide and eight-feet deep.

Sand was fused by the heat, forming a glass-like substance that would come to be known as “trinitite,” a reference to the Trinity nuclear weapon test site, about 36,000 acres in south-central New Mexico where the blast took place.

All that stood between the test site and surrounding area was a chain-link fence.

The Trinity site is about an hour’s drive from Carrizozo, the village of about 800 where Paul Pino and his extended family settled.

Even closer to the site is Bingham, population 165 and about 25 miles away from the blast.

More:Nuclear waste storage ban gains steam among New Mexico lawmakers, but Carlsbad leaders oppose it

As Pino tells it all these years later, it feels like the July 1945 explosion tore through his family too, and those of the surrounding communities.

He worried the human impact of the nuclear industry in Nnew Mexico could continue as if more nuclear projects area allowed to come to the state.

“Fix your damn mistakes before you ask us to risk anymore,” Pino said recently during an interview from his home in Albuquerque. “The money that we get from the nuclear industry is a pittance to what we pay out in medical bills and suffering.”

As he learned more about the blast and the impacts of the nuclear industry on his native community, about five years ago Pino joined with the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, an activist group in New Mexico that promotes awareness for those affected by nuclear activities and exposure to radiation.

More:Nuclear weapons development coming soon to Los Alamos National Laboratory amid safety concerns

Pino and the Downwinders join a diverse group of interests across New Mexico who’ve put aside their differences to oppose Holtec International’s plan to send nuclear waste stranded at nuclear power plants across the country to a 1,000-acre site in the New Mexico desert halfway between Carlsbad and Hobbs.

That collection of opposition includes a rare combination of environmental and Indigenous activists, state government officials and oil and gas companies who argued the placement of the underground silos will impede the ability to drill in the area, an oil-rich shale deposit known as the Permian Basin that spans from southeast New Mexico into West Texas.

“The Nuclear industry is so dirty that no one knows what to do with the garbage,” Pino says. “They know they want to send it to us. Who would keep producing garbage you can’t throw away?”

Native American groups in New Mexico have appealed to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a former New Mexico congresswoman, for help as she now oversees one of the most powerful land management agencies in the American West.

Haaland is the first Native American appointed to the cabinet and a member of the Navajo Nation and the Laguna Pueblo in northern New Mexico.

New Jersey-based Holtec received preliminary approval from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission last year to build the facility of underground silos to store some of the 83,000 metric tons of uranium presently held at nuclear power plants across the United States.

Cement and steel canisters filled with spent fuel would come by barge, truck and rail from sites across the U.S. The Holtec site would serve as temporary storage until the federal government makes good on a promise it made decades ago to find a permanent repository for the nation’s nuclear waste.

In total, it could hold up to 100,000 metric tons of the waste when fully built out.

Related:How the federal military spending bill will impact WIPP and nuclear projects in New Mexico

The NRC is expected to issue a final decision in the coming months, which will likely be followed by litigation.

Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, a Democrat, has opposed the plan, saying giving Holtec a license would amount to “economic malpractice.” Oil and gas revenue makes up roughly a third of the state’s budget and the Permian Basin remains one of the most prolific drilling regions in the nation.

The governor has also cited the “disproportionately high adverse human health and environmental effects from nuclear energy and weapons programs of the United States” suffered by Native Americans and Hispanics in the state.

To this day, there remain abandoned uranium mines in the northern and western parts of the state that are still classified as Superfund sites, drawing concerns from people in those areas that exposure to radiation could continue for generations.

In March 2021, New Mexico Attorney General Hector Balderas, citing the impact the plan would have on the agriculture and oil and gas industries, sued to block the NRC from issuing a license to Holtec.

And during New Mexico’s 2022 Legislative Session that began in January, Democrat state lawmakers Sen. Jeff Steinborn and Rep. Matt McQueen introduced identical bills in their respective chambers to prohibit high-level nuclear waste storage in the state.

The legislative effort, directly intended to prevent Holtec’s project from reaching fruition, was fought by local government officials in Carlsbad and Hobbs who hoped to bring the project and what they believed was an economic opportunity to the region.

Carlsbad Mayor Dale Janway and Eddy County Commission Chairman Steven McCutcheon co-signed a letter along with Hobbs Mayor Sam Cobb and Lea County Commissioner Jonathan Sena expressing their concerns to Lujan Grisham.

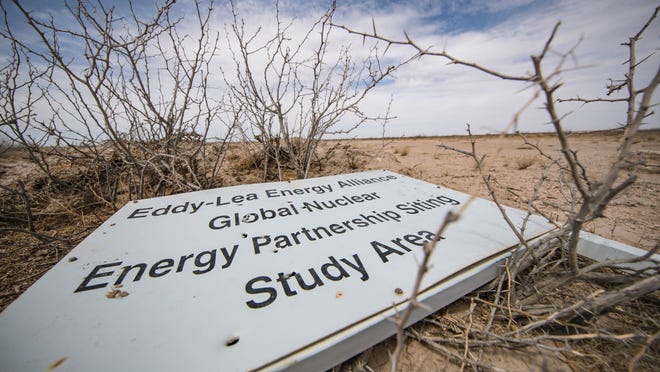

The two cities and two counties formed a consortium known as the Eddy Lea Energy Alliance which sited the project and recruited Holtec to build and operate the facility.

“Carlsbad and Hobbs as well as Lea and Eddy Counties remain resolute in their support for the Holtec interim storage facility because of the safety and security of the project,” the letter read. “This bill, if passed, may very well have serious negative unintended consequences for our national labs as well as your clean energy goal for the state.”

They also touted the economic diversity the Holtec project could bring to southeast New Mexico, along with billions of dollars in investments and hundreds of jobs.

That would be welcome, local leaders said, in a region heavily reliant on the volatile oil and gas industry.

“Furthermore, as you well know, we in southeastern New Mexico, suffer with the ups and downs of the oil industry, and this safe, secure storage facility will provide some 350 jobs as well as a $3 billion capital investment in our area,” the letter read.

“While the oil and gas industry is very robust now, it is inevitable that with the number of electric vehicles on the road becoming larger and larger, the oil and gas industry will become smaller and smaller.”

The day the bomb went off

On July 16, 1945 the world’s first atomic bomb was detonated during a test at the Trinity site, setting off a shockwave that was felt at the nearest observation point about 5 miles from “Ground Zero,” a 100-foot steel tower that held the bomb when it went off.

Radiation was believed to emanate for miles around the blast and into nearby Carrizozo.

What followed the clouds clearing and spectators departing the remote site were generations of cancers riddling the Pino family.

Pino, now 67 and a retired schoolteacher living in Albuquerque, said there were four family members living at the ranch when the bomb was detonated. He said all were impacted by different forms of cancer later in life.

His mother, Esther Lopez Pino, died at 78 after suffering from bone and skin cancer.

A brother, Gregorio, 68, was diagnosed with stomach cancer and Pino’s sister Margie had a series of nine cancerous brain tumors removed. She is presently living with thyroid cancer.

Six of Pino’s eight cousins died of cancer, and his daughter was diagnosed with skin cancer.

Nieces and granddaughters have since developed thyroid cancers.

“She suffered horribly,” Pino said of his mother. “She was a tough rancher woman, but she suffered.”

And Pino believes all the suffering and death can be tied back to that fateful day at the Trinity Site.

“They had people there in town monitoring and the Geiger counters went off scale within eight hours of the blast,” he said. “They had incredible amounts of radiation.”

One of Pino’s cousins Bernice Gutierrez, 76, a retired social worker also living in Albuquerque was born eight days before the Trinity blast in Carrizozo.

Her grandfather had stomach cancer, her mother had thyroid, skin and breast cancers, and Gutierrez’s brother and his daughter both suffered from thyroid cancer.

In June 2021, Gutierrez’s oldest son Toby Gutierrez Jr. died of Leukemia after receiving a bone marrow transplant and living on a ventilator.

Doctors recommended Gutierrez have her thyroid removed due the high rate of diagnoses in her family and she did so.

“I think it’s an unnecessary evil,” Gutierrez said. “I think New Mexico has been viewed as a dumping ground. The State of New Mexico has become a sacrifice zone. I think the government has used us as their dump site for nuclear.”

Gutierrez views Holtec’s plan as the continuation of an industry that already brought generations of sorrow to her people and one that should be stopped and relocated.

“They think of us as indispensable,” she said. “They have to. We are not important to them. All we’re good for is to have a site, an area where they can dump their nuclear waste. We have to fight that. We’re a sacrifice zone for New Mexico and that has to end. We cannot be viewed as indispensable people.”

‘We’ve been neglected.’

For Pino and Gutierrez, part of healing from the Trinity blast and New Mexico’s nuclear legacy could come in the form of federal compensation.

Through the Tularosa Basin Downwinders the cousins hoped to see an expansion of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), a law enacted in 1990 to provide cash payments to those impacted by America’s nuclear weapons legacy.

The Downwinders hope to make New Mexicans and the people of Carrizozo eligible for compensation under the Act.

As it is currently administered by the U.S. Department of Justice, the RECA offers one-time payments to uranium workers across 11 western states including New Mexico.

It also offers payment to “downwind” counties believed close enough to nuclear weapons test sites like Trinity to be impacted by radiation exposure.

Areas in Nevada, Arizona and Utah qualify for downwinder payments, but New Mexico is excluded and thus so are the ranchers of Carrizozo.

“People in Carrizozo are super patriotic,” Pino said. “It’s a shame we’ve been neglected after they tested a nuclear bomb on us.”

A bill was introduced by U.S. Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez (D-NM) in September 2021 aimed at expanding RECA payments to New Mexicans, supported by U.S. Rep. Yvette Herrell (R-NM) and a companion bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate with Sen. Ben Ray Lujan (D-NM) listed as co-sponsor.

“New Mexicans have endured the harmful effects of nuclear testing and uranium mining for decades,” Leger Fernandez said in a statement. “These aren’t abstract issues for New Mexicans. Our communities, especially communities of color, suffered when we tested nuclear weapons and mined uranium for those bombs on our lands. Our government must right this wrong.”

Lujan said the bill and compensation for New Mexicans suffering the effects of radiation exposure was long overdue.

“While there can never be a price placed on one’s health or the life of a loved one, Congress has an opportunity to do right by all of those who sacrificed in service of our national security by strengthening RECA,” he said.

To Pino, cash given under RECA does little to make up for the damage, but it would signal to him an apology by the American government and acknowledgment of what his hometown sacrificed for the sake of military might.

“There’s so many people that have already died. They could apologize and they could make us part of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act,” Pino said. “We were the first people on the face of the earth to be exposed to radiation from a nuclear bomb.”

He said several Carrizozo residents and former residents would today qualify for the funds that could offset medical bills and help raise many New Mexicans out poverty – a widespread issue in the rural state.

“It would change the economic face of New Mexico for generations. If you give a Chicano in New Mexico $150,000 it would go into their local community next week,” Pino said. “We’re not going to put it in a bank or some kind of investment. Maybe that would keep us from always being at the bottom of everything.”

Adrian Hedden can be reached at 575-618-7631, achedden@currentargus.com or @AdrianHedden on Twitter.

[ad_2]

Source link