[ad_1]

|

An aerial view of Hermosillo, Mexico, which is miles from the Sonora lithium mine and home to a Ford Motors manufacturing plant. |

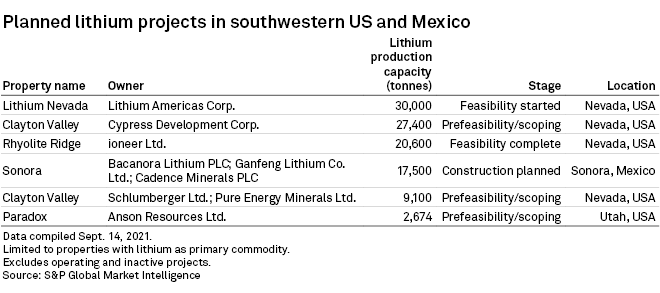

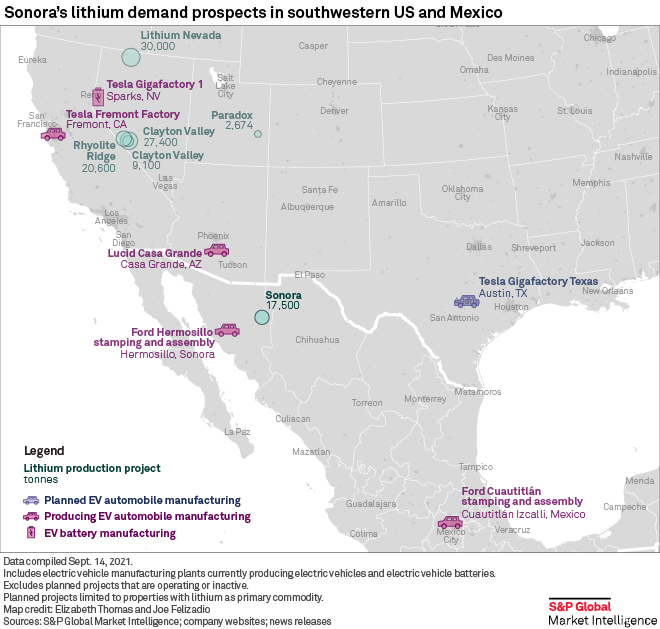

In 2015, the discovery of a massive lithium deposit south of the U.S. border led electric vehicle giant Tesla Inc. to announce a deal with Canadian miner Bacanora Lithium PLC. The automaker agreed to buy an undisclosed amount of lithium chemicals for its Nevada Gigafactory from Bacanora’s proposed mine in the state of Sonora in northwest Mexico, creating the potential for a new branch of the North American battery supply chain.

Under the arrangement, the mine had to meet an undisclosed timeline with performance benchmarks. Now, six years later, it is unclear whether Tesla will ever get lithium from its deal with Bacanora.

The mine, also named Sonora, is the 12th-largest lithium project under development in the world based on primary reserves and resources and holds a total in situ value of $22.6 billion, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. But it carries unique risks; Bacanora plans to use an unproven extraction process to remove lithium from clay stone, and the project is in territory controlled by drug cartels and plagued by violence associated with the cross-border drug trade and human trafficking.

“U.S. regulatory hurdles might set you back a year or two, but a cartel will shoot you in the head,” Emily Hersh, a lithium industry expert and managing partner with DCDB Group, an international consultancy, said in an interview.

Another source

If the electric vehicle revolution finally comes to fruition in the U.S., deals between U.S. automakers and miners across North American could prove crucial for ensuring that EV and battery manufacturers avoid the sorts of hiccups seen in global supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Making matters more complex, the U.S. is heavily reliant on imports for much of its lithium supply as well as other minerals the government considers significant for national security.

Like Canada, Mexico could hypothetically satisfy U.S. demand for lithium. But for now, Tesla’s involvement with what is the only lithium mine in Mexico has apparently ended.

|

|

|

|

This story is part of a series examining challenges faced by mining companies and other operators in South America amid the global energy transition. Turmoil casts doubt on Latin America’s mining of energy-transition minerals Facing headwinds, Chilean miners mount aggressive expansions Rich in renewable energy, Chile seeks to become global hydrogen powerhouse $22.6B Mexican lithium mine bogs down in drug cartel, tech risks |

|

Bacanora Company Secretary Cherif Rifaat did not say whether the Tesla deal has been canceled, and Bacanora did not respond to requests for further comment. Tesla did not respond to multiple requests for comment by S&P Global Market Intelligence. The company reportedly dissolved its press relations team in late 2020. Bacanora did not discuss the 2015 deal in its most recent annual financial filing to shareholders released in March and has not mentioned the matter in recent presentations for investors. Asked whether Tesla is still involved with Bacanora, Rifaat would only say the company has 100% off-take agreements with Japanese metals trader Hanwa Co. Ltd. and Chinese lithium miner Ganfeng Lithium Co. Ltd., which is set to take control of Bacanora pending approval from shareholders and Mexican antitrust authorities.

On paper, agreements like the one between Tesla and Bacanora could make sense for companies with big EV plants in development in northern Mexico and the U.S. Southwest. In northern Mexico, a region with fewer government permitting requirements than the U.S., it should be easier to get new mines online.

But Tesla’s departure from northern Mexico would serve as a warning of the risks that any EV company will face if they try to procure battery metals from lawless and dangerous regions, Hersh said.

Danger zone

The U.S. government has warned citizens to avoid travel in Sonora, which for years has been effectively controlled by the Sinaloa cartel, the gang that was until recently run by infamous Mexican drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

According to the U.S. State Department, the Sonora state is a “key location” for international drug trafficking and human trafficking networks. Mexicans frequently go missing in the state, including Mexican Indigenous persons, a crisis that U.S. and Mexican officials have linked to criminal actors.

While much crime in Mexico goes unreported, data indicates violence around the mine is on the rise. Statewide homicides hit a record high in 2019, dipping slightly in 2020 despite societal lockdown measures to protect against the spread of COVID-19, according to Control Risks, a global consulting firm.

Murder rates in Mexico are “likely to remain relatively stable” over the next five years, Control Risks said in a February 2021 outlook for the Latin America region. The government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has done little in response to persistently high violent crime, the group said.

“The current strategy will prevent meaningful improvements in the security environment during 2021,” the February report stated.

Authorities are especially nervous about cartels targeting mine infrastructure and supply lines. The risk to mines from cartels has risen so high that the Mexican government began deploying a specialized police force in September 2020 to help companies protect mines.

While environmental risks are also associated with the project, including drought impacts, the local population is too focused on safety to raise objections to potential struggles over scant water supplies, mining activist Jennifer Moore said in an interview.

“The mine is in a difficult area, so there has not been community outcry about it,” said Moore, an associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies who coordinated Latin American campaigns for 18 years at MiningWatch Canada, a nonprofit advocacy group.

“[That] part of Sonora is quite disputed territory,” Moore said. “There’s not been serious measures to protect people, and the number of assassinations and disappearances just keeps going up.”

The ‘new oil’ of Mexico

The Sonora project also faces technological and political hurdles.

Clay lithium deposits such as Sonora are “unconventional” lithium resources that lack cost-competitive mining technologies compared to mainstream lithium mining, such as salt brine extraction, BloombergNEF analyst Sharon Mustri told S&P Global Market Intelligence. “It’s not proven yet that it will be economic, that the process will extract lithium in the way they’re planning in their flowsheets.”

Other lithium miners have staked their futures on clay lithium deposits. Lithium Americas Corp.’s Thacker Pass mine, also known as Lithium Nevada, is in northern Nevada and would also involve processing raw lithium from clay. But the project is running into hurdles during the permitting process as environmentalists and Indigenous populations raise concerns about impacts on water and endangered wildlife, and the Biden administration could place additional restrictions on the project through proposed bird habitat protections.

In addition to its stake in the Sonora project, Chinese lithium miner Ganfeng also holds a 12.5% stake in Lithium Americas. Amid the potential for regulatory setbacks, the Mexican deposit gives Ganfeng an opportunity to possibly reach U.S. auto markets with fewer regulatory burdens, BloombergNEF’s Mustri said.

And Mexican officials, who have termed the country’s lithium reserves “the new oil,” have also shown a determination to exert more control over lithium development. In 2020, López Obrador floated the idea of nationalizing Mexican lithium reserves, and in October 2020, López Obrador said the government will deny future lithium concessions to new private mine developers.

‘Contributing to conflict’

Technical difficulties and political maneuvering aside, the risk of gang violence may deter U.S. automakers from sourcing lithium from the Sonora mine.

If Tesla and other automakers obtain lithium chemicals from Sonora, they would present a new argument for activist investors seeking more transparency from the EV supply chain on human rights, said Anneke Van Woudenberg, executive director of RAID, a U.K.-based nonprofit organization focused on corporate responsibility.

Van Woudenberg compared the risk to a potential repeat of the backlash automakers and tech companies faced after reports of child labor at cobalt mines in Africa linked to global lithium-ion battery manufacturers. “I’ve never dealt with gang violence in terms of human rights issues. But what I can tell you is, they should not be contributing to conflict and human rights abuses,” Van Woudenberg said.

Bacanora’s Rifaat did not comment on safety concerns raised about the the mine’s location. The company secretary referred Market Intelligence to a recent company presentation on environmental, social and governance issues and Bacanora’s most recent annual financial report, which in a footnote cautioned investors that successful development of the mine could be stymied by disruption from cartels.

Neither document stated how the company would minimize the risks presented by cartel activity around the mine.

[ad_2]

Source link

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/M4O2GCFNPNJNRAFOME2WYD3OAA.jpg)