[ad_1]

The first to die were Chinese agricultural workers, who were killed in the orchards and gardens surrounding the Mexican city of Torreón by advancing revolutionary forces in the early hours of 13 May 1911.

After skirmishes at the outskirts of the city, the outnumbered federal garrison abandoned their positions and slipped away under the cover of darkness.

As the rebels entered the city, they were joined by thousands of locals, fired up by racist speeches. A herb-seller is said to have clutched a Mexican flag and screamed: “Let’s kill the Chinese!” A revolutionary commander, Benjamín Argumedo, is believed to have fired the first shot.

Over the next 10 hours, the mob sacked Chinese-owned businesses, looted the Chinese bank and dragged their Chinese neighbours by their distinctive braids, trampling them to death with horses.

“Argumedo gave the order to kill the Chinese,” said Julián Herbert, author of a history of the massacre. “But everyone joined in the killing. It was soldiers, men, women – everyone.”

A total of 303 Chinese people were murdered in the massacre at Torreón, then a burgeoning railway town some 500 miles south of the US border. Afterwards, rebels and locals posed for photographs with the bodies of their victims before they were hauled away by the cartload.

The savagery was an appalling expression of a wave of anti-Chinese racism which swept throughout North America in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the US such sentiments led to the Chinese Exclusion Act banning the immigration of Chinese labourers; in Mexico they culminated in the expulsion of most of the country’s Chinese population in the 1930s.

The Torreón massacre caused indignation in China, and Mexico eventually agreed to pay 3.1m pesos in gold in reparations, although the payment was never made.

In Torreón, nobody was ever charged – let alone tried or convicted – over the massacre, and today the events of 1911 remain largely unmentioned.

There are no monuments marking the tragedy and attempts to commemorate the events have been met with resistance.

“This matter of the Chinese killings makes us confront a truth that we haven’t wanted to talk about locally,” said historian Carlos Castañón, who oversees the municipal archives.

On Monday, however, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador is expected to travel to Torreón to seek forgiveness for the massacre as part of a year-long series of events marking some of the darker chapters in Mexico’s history, including the 500th anniversary of the fall of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán.

“It’s an honest gesture, which transcends politics,” said Castañón. “For the first time, we’re going to confront the big lie that we’ve perpetuated – and the silence of our complicity.”

In Torreón that silence is still so absolute that no monuments mark the massacre, which killed half the city’s Chinese population at the time.

A commemorative plaque was swiftly stolen. A statue erected in a public park in 2007 was vandalized and later removed, but will be restored to a public plaza for the commemoration.

Victims of the massacre were buried in common graves, including one which is now covered by a roadway and small playground.

“Local historians considered this just an anecdote: ‘One day in Torreón they killed some Chinese people’,” said Castañón, who has combed through archives in an attempt to learn more details of the massacre, including the victims’ names.

The president’s plan to commemorate the massacre has predictably ruffled feathers among some in Torreón.

“All of humanity would have to apologise for what’s happened through the centuries,” groused the then mayor, Jorge Zermeño, in February, according to the newspaper El Sol de la Laguna.

“We will participate [in the ceremony] but we will have our own opinion,” he said. “I think that in wars, there’s a lot of confusion. These are events of the time and have to be seen in the context of which they occurred. Of course they were regrettable.”

Much of that grumbling stems from Torreón’s “foundational myth” as a city of hardy immigrants who conquered the desert, said Javier Garza, a former newspaper editor in the city.

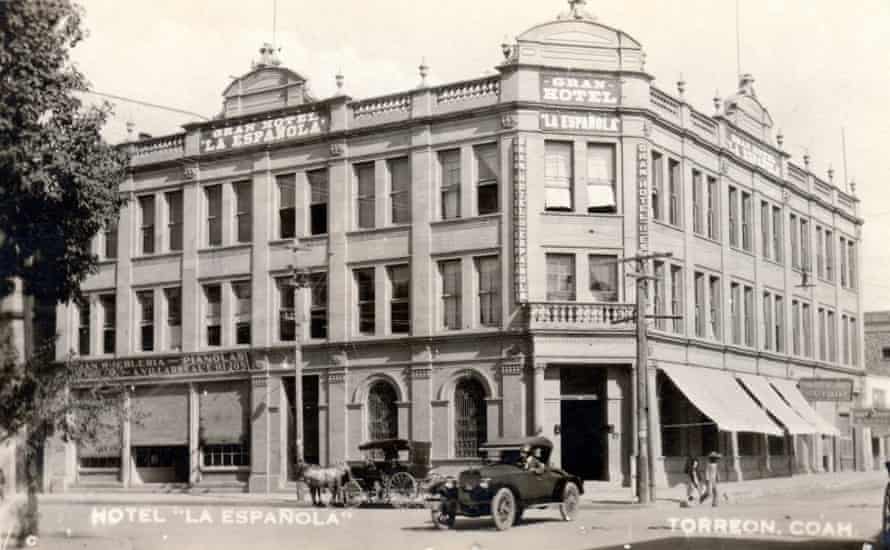

Before the massacre, Chinese migrants opened a bank, built a tram connecting Torreón with the neighbouring city of Gómez Palacios and ran most of the local laundries. Their farms fed the local population.

“The Chinese community [in Torreón] was the most prosperous [Chinese community] in Mexico,” Herbert said. “It wasn’t the most numerous, but it was the most prosperous.”

In his book The House of the Pain of Others: Chronicle of a Small Genocide, Herbert disputes the local narrative that the pogrom was a spontaneous uprising by poor Mexicans, arguing instead that anti-Chinese racism was rife in Torreón – and across the country. Herbert’s conclusions proved so controversial that he was unable to hold an event promoting the book in Torreón.

Not all locals participated in the massacre: some, including a local lumberyard owner sheltered Chinese residents from the mob. Most of the survivors fled Torreón, though some later returned, and the local Chinese community now numbers about 1,000.

Some in the Chinese community still seem reticent to speak of the massacre, even as they express pride in their role of building Torreón into a city famed for industry and agriculture.

“I think [Amlo’s] visit is important and the event merits this. But the [Chinese] community is not requesting it,” said Antonio Lee Chairez, 90, whose father Juan Lee survived the massacre with the help of neighbours.

“But it has to be positive [that he is coming] – because this was an outrage that nobody ever admitted.”

[ad_2]

Source link